(Judge Dredd Megazine, Rebellion)

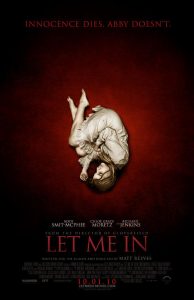

Let Me In (out now), as readers of this column must surely know, is the English-language remake of the hugely acclaimed Swedish film, Let the Right One In. It’s a lyrical tale about a tender and bloody love between a boy and a… Well, skip to the next review if you don’t want spoilers. If you’ve seen Let the Right One In, then you won’t have many surprises, except for the high calibre of names associated with this remake. The director is Matt Reeves, who so capably reconceived Godzilla for a post-9/11 Manhattan as Cloverfield. The boy protagonist is played by Kodi Smit-McPhee, who wandered a dour post-disaster America with Viggo Mortensen in The Road. As for the girl who insists she’s not a girl, she’s Chloe Moretz, still blood-hungry after the potty-mouthed carnage of Kick-Ass. At this rate, Hit Girl will have passed Schwarzenegger’s body-count before she’s sixteen.

As in Let the Right One In, the film’s action takes place in a landscape where snow powders the black night, twelve year-old Owen is bullied mercilessly at school, and a sad, self-possessed girl called Abby turns up on a climbing frame. One obvious difference is the setting; instead of Stockholm, it’s Los Alamos, New Mexico, with President Reagan on television in 1983. “Do you know where your children are?” demands a late-night TV caption, getting the film’s biggest laugh. Meanwhile, a luckless townsman is hung upside-down like a butcher’s slice and gutted in the snow.

Older horror fans know this murder modus operandi was used in a vintage vamp film, Dracula – Prince of Darkness (1966), by Britain’s Hammer Studio. Nearly fifty years on, Let Me In appears under the banner of a relaunched Hammer, with a comic-strip style logo shamelessly ripped off from Marvel’s flipbook. It’s worth remembering that Hammer made its horror name with what were, effectively, remakes: crucially, The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) and Dracula (1958), both brands associated with Universal in the ‘30s and ‘40s.

Hammer, though, told the stories in radically different ways. If you watch The Curse of Frankenstein next to Universal’s 1931 Frankenstein (the one with Boris Karloff), it’s hard to believe they’re “based” on the same novel. Let Me In is not such a remake. If it would be unfair to call it slavish, it certainly feels very familiar to anyone who’s seen Let the Right One In, so that it can be rather tedious watching it and waiting for some fresh take on the text. There’s no “neutral” way of watching; someone who’s seen Let the Right One In will have a completely different experience from someone watching Hammer’s film new.

In itself, Let Me In is a fine, interesting picture; the fears that it would be dumbed or watered down are unfounded, while the young leads are as good as their track-record. Abby goes through several transformations in the film, though perhaps the most lyrical is her first, from a wan, gaunt waif, her stomach growling uncontrollably, to a girl who almost shines after she’s fed. Some of her more monstrous moments don’t quite work, but nor do they ruin the film. Her vampiric motions are twitchy and unearthly, but you can’t feel their uncanny reality, the effects themselves are too fake. More visceral are the assaults on Owen by the school bullies, amped up from the first film so that you readily agree these goons should die.

Richard Jenkins, soon to be seen in the horror comedy The Cabin in the Woods, is effective as Abby’s mysterious so-called “Father,” whom we first see as just a pathetic slave (like Dracula’s Renfield) but who has surprisingly tender scenes of his own. Much of the time, though, he’s harvesting food for his mistress, a grotesque black binbag over his balding head. One of the big “new” scenes, with no counterpart in the first film, has overtones of Hitchcock’s classic black humour as Father learns that car boots don’t make good hiding-places. It ends with a wincingly convincing collision and the giddy sensation of being flopped down a hill in a rolling wreck of metal.

There are also traces of Hitchcock’s Rear Window in the way Owen spies on his neighbours through his telescope, his voyeuristic peepings prompting strange new yearnings in the “innocent” boy. Less successful are the clunky references to Romeo and Juliet, which Owen happens to be studying at school: Bonnie and Clyde would have fitted better. Appropriate to the title, there’s lots of banging on doors, and fearful approaches towards them (a fearful backing off, too). The tensest sequence, even if you’ve seen the original, is when an adult breaks into Abby’s room and puts you in the position of fearing for both parties. Many of the shots are child’s-view subjective, with background details and characters as blurs, and the children’s meetings often gleam with a perversely heavenly light.

One of the remake’s new motifs is the fight between religion and amorality; the TV shows Reagan’s keynote “Evil Empire” speech, where he declared, “There is sin and evil in the world…” Later on, Owen, agonised by what he has learned, phones his father (who’s never seen) and ask him if there’s indeed such a thing as evil. Although Reeves said this was inspired by a scene in the Satanic thriller Rosemary’s Baby, it reminded me of a story about Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining, another snowy mood-piece. The tale goes that Kubrick made a midnight call to Stephen King, who wrote the Shining book, and asked if he believed in God. King supposedly said yes; Kubrick said “I thought so,” hung up and proceeded to make the most Godless horror imaginable.

None of Let Me In’s new touches really make a deep difference to the film… or do they? Some reviewers have argued that a few details refocus everything, in the manner of Blade Runner’s unicorn. One such detail involves a photo (though it really just confirms what many viewers would think anyway), while another involves a (playful? ominous?) rhyme sung at the end of the film. For me, though, the conclusion stays ambivalent, irrespective of what Matt Reeves says in the eventual DVD director’s commentary. Cynics will read the outcome one way, and romantics another.

Certainly, there are no stupid additions, like the bit in the American Ring remake where a character spectacularly electrocuted himself for the hell of it. The keynote scenes (Owen asking Abby if they can go steady as they platonically share a bed, or that underwater finale) feel almost unchanged. However, we lose the support cast of gnarly barflies who gave the original its local colour, while the kids feel more normal, less ethereal and unworldly than their Swede counterparts. Which is another way of saying that viewers who loved the first film will probably find this one inferior. Anyone else won’t care, and should enjoy it greatly.

(c) 2018 Rebellion A/S. Reprinted with permission.

[amazon_link asins=’B00ESQF6AQ,B004DCAD94′ template=’ProductGrid’ store=’anime04c-21′ marketplace=’UK’ link_id=’f5975de3-0c9a-498e-9230-8898564e29bb’]