(Sight & Sound, BFI)

Phuket, six months after the Asian tsunami. A couple, Paul and Jeanne, are devastated by the disappearance of their young son, Joshua, in the disaster. Jeanne sees video footage shot in Burma, and insists that a boy glimpsed with his back to the camera is Joshua, whom she thinks was trafficked. Paul is unconvinced, but Jeanne persuades him to pay a guide to take them to Burma.

Vinyan comes from Fabrice du Welz, the director of Calvaire (2004) and Benoît Debie, the DoP of Irreversible (2002), so it’s little surprise that their new film is an uncomfortable, confrontational watch. Stark white-on-black opening credits evoke Irreversible, before giving way to an art-installation abstraction of catastrophe. Murky depths turn from black to red; there are myriad bubbles and motes of light; and synthesised screams rise to the first of Vinyan’s many aural crescendoes.

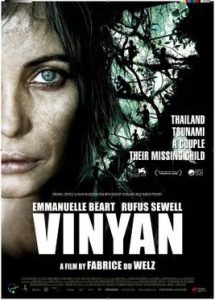

At least ostensibly, the film is dealing with the aftermath of the Asian tsunami, though it’s hard to imagine a bigger contrast with Aditya Assarat’s low-key Wonderful Town (2007) which opened here recently and took on the same subject. The protagonists in Vinyan are a shell-shocked Western couple (played with impressive dedication by Emanuelle Béart and Rufus Sewell), whose young son vanished in the disaster. The mother glimpses a boy in a video, his back to the camera, and insists he’s her son. The father has lost hope but goes with her, eventually reaching a dark place where grinning boys spring from guilt and grief.

Smeared in mud, these boys are all but interchangeable, and the script highlights how Sewell’s character Paul comes to see them as monstrous ciphers – an irony for a man seeking one child from countless thousands lost. (When Paul is presented with one boy and protests that it’s not the one he’s looking for, someone else shrugs, “What’s the difference?”) Yet for British viewers at least, the tsunami background can seem almost incidental to Vinyan, given its resonances with smaller tragedies. The guilt-ridden parents make us think of the McCanns. Glimpses of the missing child in a Manchester United top evoke the iconic photo of Holly Wells and Jessica Chapman, from the last day of their lives.

The figure also evokes the red-coated phantom in Don’t Look Know (1973), only weeks after Michael Winterbottom’s Genova invited comparisons with Roeg’s film. Early on in Vinyan, there’s a powerful night sequence in which Paul pursues his distraught wife through a Phuket marketplace, the surrounding sound coming and going kaleidoscopically as it did in Genova’s narrow alleys. Winterbottom was criticised for (supposedly) betraying viewers’ expectations of a tragic ending, but Vinyan’s bleak course never lets up, finally leaving believable drama for the grand guignol of Cannibal Holocaust and Apocalypse Now.

For auteurists, Vinyan might be a manipulative reconfiguring of du Welz’s Calvaire, which mixed nastiness and hilarity like a gross campfire tale. In Calvaire, a male victim for whom we cared little was dressed up as a madman’s dead wife, putting metatextual weight on his status as a cipher. Vinyan features two people who feel far more “real” to us, being put through a similarly manic and gruelling journey. Is this a Haneke-style funny game? Perhaps the tasteless question thrown at Paul, “What’s the difference?,” is also being posed to viewers who laughed at Calvaire, but who will find no amusement here.

On its own terms, Vinyan suggests that parents who cannot “let go” of a lost child doom themselves to hell, yet one character remembers finding a living baby in a mass grave, a story to keep desperate parents searching forever. Vinyan’s first half grips largely thanks to Béart and Sewell (and certainly not because we hope, as in a film like Changeling, there’s any chance the boy will be found). But as their ordeal continues, all the filmmakers’ effectively blunt cuts (from nightmares into the midst of “real” scenes), audacious camera shots (a swoop down into a flood-ruined building) and beautiful transitory details (boys playing in shadow; a held shot of a tree standing in water) fail to compensate for Vinyan’s mean-spirited familiarity.

[amazon_link asins=’B002IEVLAO’ template=’ProductAd’ store=’anime04c-21′ marketplace=’UK’ link_id=’b52ce039-ace7-11e8-9a94-b125078c6061′]