(Sight & Sound, BFI)

[This article was written in 2009. Both interviewees – Dickie Jones, the voice of Disney’s Pinocchio, and puppeteer Bob Baker – died in 2014.]

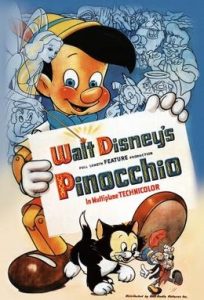

As Disney’s classic Pinocchio is released on DVD and Blu-Ray, Andrew Osmond meets the man who was the puppet.

Early on in Disney’s 1940 cartoon feature Pinocchio, a winged Blue Fairy in a sparkly dress touches her wand to a wooden boy marionette and declares, “Little puppet made of pine; Wake, the gift of life is thine!” Pinocchio wakes amid sunbursts, stretches and blinks his blue painted eyes, and we cut to the gnomelike spectator Jiminy Cricket, voiced by vaudeville star Cliff Edwards. Jiminy looks at us, lets out an impressed “Phew!” and chirps, “What they can’t do these days!” You can almost see Walt Disney’s ghost beam with pride at his cartoon magic.

It’s entirely fitting that Pinocchio is being revived on DVD and Blu-Ray just as the Disney studio heads in two directions. On the one hand, Disney’s 3D CGI cartoon Bolt is playing in cinemas; on the other, the studio is finishing The Princess and the Frog, its first traditionally-animated cartoon for a while, to be released next Christmas. But Pinocchio linked handicrafts and hi-tech, taking them to levels of craftsmanship unsurpassed in the next seven decades. The film embraces the artistic and technical cross-currents, even contradictions, that pervaded animation then and now.

We can’t know what Walt would have thought of Bolt as a film, but he would have surely been fascinated by its three-dimensionality, something he spent thousands of dollars striving for. In Pinocchio, he created ostentatious travelling shots using the multiplane, a giant camera holding multiple glass sheets on which cels, backgrounds and overlays were painted separately (much as Willis O’Brien had created King Kong’s Skull Island from multi-level dioramas a few years earlier). Pinocchio’s big multiplane shot shows an Alpine village awakening on the morning after the puppet’s “birth,” as we swoop and turn overhead like a bird.

There’s another foreshadow of modern technology in the archive footage in the DVD extras. We see actors dressed as Pinocchio’s characters, performing on almost bare stages, perhaps following chalk outlines or using stand-in props (a sandbag substitutes for a cricket-scaled lump of coal). The footage was reference for Disney’s artists, but now it looks like the ancestor of such computer-age techniques as bluescreen and motion capture.

The voice and reference model for Pinocchio was Richard “Dickie” Jones, who started in showbiz aged four. He was billed in rodeos as the “World’s Youngest Trick Rider and Trick Roper,” and he caught the eye of Western film star Hoot Gibson. Jones’ film career began in 1934. Days before he started work on Pinocchio, he was acting in a “Hopalong Cassidy” Western called The Frontiersmen, which also featured Evelyn Venable, the voice of Pinocchio’s Blue Fairy. Over the eighteen months that Jones worked on Pinocchio, he found time to act in six more live-action films.

“It was a tough job for me, because I didn’t like being cooped up,” a genial Jones remembers of Pinocchio. “That’s why I liked Westerns so much, when I was outdoors all the time. The other studios had places I could go and hide, and play on the sets… Warner Brothers had all the ships from Captain Blood (1935) on Stage 13, and I’d go out there and climb over them so my teacher had to find me. I couldn’t do that at the Disney studio.”

Jones compares the voice-acting in Pinocchio to a radio show. “We were on the soundstage, looking at the control room where the director and Walt were.” (Pinocchio had two supervising directors, Ben Sharpsteen, who made Dumbo (1941), and Ham Luske.) “I don’t think we did more than two or three takes on any one scene,” says Jones. Today, voice-actors on cartoon films often record in isolation, but Jones was able to play off his fellow actors, especially Edwards. “They had to sit on him, because he would keep me laughing all the time… I couldn’t concentrate on my work,” Jones remembers. “He never went anywhere without his ukulele, so when he wasn’t doing anything, he’d start strumming on it and singing songs.

Walt was present for all of Jones’ scenes. “When he was around, he was the boss, telling the director what to tell me. I just thought of him as a great big tall man, a nice guy. He taught me how to throw pushpins [which were used to pin up storyboard drawings], and we’d have contests to see who could score the highest. I never beat him.”

When I asked Jones if his eleven or twelve year-old mannerisms were picked up by the animators, he suggested looking at the “An Actor’s Life for Me” song sequence, in which Pinocchio is ushered onto the wrong road by a devious fox, voiced by Walter Catlett, another vaudeville stalwart. “The animators stood with their hands in the air, they couldn’t figure out how to do (the scene). So they dressed us in costume and built a set with the road and we acted the scene out two or three times and they said, Okay, now we’ve got it… But they would have a little camera, focused where they could get my nose, my mouth and my chin in every scene, so they could incorporate that in every frame and get the right movement.”

The great Disney animators who worked on Pinocchio are gone now (the last was Ollie Johnston, who died in April 2008). One man who knew them was Bob Baker who, like Jones, first visited the studio as a child. Baker was acquainted with Walt and his daughters, and would later become a puppeteer, handling a puppetry scene in Disney’s 1975 live-action Escape to Witch Mountain, remade as this year’s Race to Witch Mountain.

When Pinocchio was made, the studio was still based at Hyperion Avenue in Los Angeles. Baker remembers, “Pinto Colvig (the original voice of Goofy) would be in there, humming a tune, and one of the animators would be trying to figure out what they were going to do in a certain sequence; someone would say, “I’ve got an idea,” and they’d look at the storyboard and ask Walt what he thought… It was a community atmosphere.” Just as Pinocchio was finishing, the studio moved to a far more expansive site in Burbank, where it remains today. “(The animators) hated it when they came over there, because they were all separated,” Baxter said. “You need people projecting things back and forth to get things working.”

Baker describes Walt himself as “like a train on a track. He had one idea and he just kept staying (with it)… He was moody in many cases, and he would get angry at times. He wanted his artists to be the best artists of all. They used to get very upset with him and say, ‘I can go out and get a better job than this,’ and he’d say, ‘Yeah, but you wouldn’t be pushing a pencil and that’s what you like to do…’ A lot of people didn’t like him because they felt he was the father image, but that’s it, he was. He knew what he wanted and he wanted his artists to do it.”

Whereas Disney’s first animated feature, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) was a hit, the costlier Pinocchio haemorrhaged money, with the studio eventually writing off a million dollars of its budget. War in Europe blighted Pinocchio’s foreign sales, while some critics still argue that the film was too dark for American viewers. Pinocchio himself almost rushes from one nightmare to the next, the worst being Pleasure Island where delinquent boys are transformed into donkeys.

Baker, though, argues that American audiences had been “spoiled” by the first feature cartoon to compete with Disney. The Fleischer studio’s Gulliver’s Travels beat Pinocchio into the cinemas, opening a few weeks earlier in Christmas 1939. “People didn’t like it, it wasn’t like Snow White,” Baker argues. “Gulliver ruined Pinocchio’s sales; people didn’t want to go and see another jiggly animated film.” (In fairness to Gulliver’s Travels, it was “at least modestly profitable” in its day, unlike Pinocchio, according to Michael Barrier’s book, Hollywood Cartoons.)

For some viewers, the aesthetics of Pinocchio died with CGI. For all the 3D pretensions of computer animation, Jones finds the new medium flat. “It has no life to it. Snow White had a lot of life to it, and Pinocchio came out 100% better, and then it just got better and more lifelike. But then they found out they could push buttons…” Other critics, such as Barrier, maintain that Pinocchio was already betraying the spirit of cartoons, through its over-reliance on live-action.

For most viewers, Pinocchio will be a bracing reminder of animation as it once was, from the vibrant brushstrokes and Germanic carvings of the toymaker’s home, to the flaming white foam that flies off the gargantuan whale Monstro in the tumultuous climax. For me, it was especially gratifying to see Pinocchio full size at Hollywood Boulevard’s El Capitan Theatre, another venerable institution restored by Disney. The El Capitan screening had extras not on Blu-Ray; palatial architecture, an organ rising through the floor and even Pinocchio in person, dancing live on stage.

[amazon_link asins=’B00H36DOP2,B00838HRP2′ template=’ProductCarousel’ store=’anime04c-21′ marketplace=’UK’ link_id=’689081c6-ace1-11e8-a864-fdc262c2b0ab’]