(My review of the 1998 Berserk TV series, published in Neo magazine, is below; my reviews of the film versions are underneath.)

In a medieval-style world, as brutal as Game of Thrones, the ragtag Band of the Hawk wins acclaim on the battlefield. It’s led by the beautiful, charismatic Griffith, his devoted right-hand woman Casca, and the hulking swordsman Guts, all headed towards doom…

Great anime tragedies can be as intimate as children living in a cave of fireflies, or they can be as epic as the French revolution of Rose of Versailles. Berserk – and specifically the long Berserk storyline called “The Golden Age” – is as epic as Versailles, though it’s set in an imaginary Middle Ages. Berserk has monsters and otherworlds, and its action crescendos in a blood-drenched deus ex machina, but they’re a small part of its story. Primarily Berserk is a bisexual love-triangle between three damaged human heroes, two men and a woman and the idealistic army they lead. Together, they’ll change the world in a horribly ironic way.

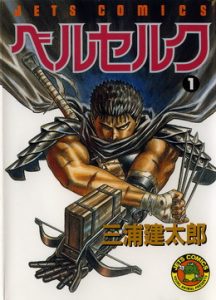

Both anime versions of “The Golden Age” are reissued this month. One is the glossy-looking twenty-first century film trilogy, released in a Blu-ray box-set by Manga Entertainment. But we’re looking at the earlier 25-part TV version from 1997, debuting as a Blu-ray set from MVM. Rewatching the series, there’s no doubt – it’s far, far better than the films.

The TV animation may look old and ugly at first, but then you’re sucked into a story that, for all its campy, rip-roaring elements, feels more like literature. Amid the huge battles, many of the best scenes are the characters’ eloquent speeches, even soliloquies, about their drives and dreams. Never has a gorefest had so many tearjerking scenes. Nor has it had so many iconic character moments, from the Freudian campery of Guts lying on a roof, pointing his massive phallic sword at the moon, to an amazing image of his master Griffith standing naked in a river, tearing his flesh with his nails in penance to the dead.

Crude as the art looks, it often rises in pivotal scenes with strong compositions and pacey fights. It’s also lifted tremendously by the sad yet soaring music of Susumu Hirasawa, a frequent collaborator with Satoshi Kon, though Berserk’s punkish title theme is endearingly dreadful.

This version is notorious for its jagged shock ending. There’s a different, though unsatisfactory, resolution in the last Berserk cinema film (The Advent); it’s taken from the Miura manga, as are the Berserk TV sequels now being made in Japan by other hands. But honestly, there’s a strong case for seeing the first anime Berserk as complete in itself, shock ending and all. In which case, we advise you to skip the first episode (which isn’t very good anyway) and jump in at part 2, which is the real start of this magnificent story.

(I wrote a brief review of the first Berserk film, The Egg of the King, in SFX Magazine, Future Publishing.)

… The film looks spectacular, mimicking a live-action blockbuster, despite clunky mixing of 3D and drawn animation. The drama is sometimes clumsy, often powerful, and certainly an original vision. The biggest problem is this is essentially act one of a three-part movie, and it suddenly ends midway through the story.

(My review of the second film, The Battle for Doldrey, was in Neo magazine.)

Once upon a time in fantasy movies, swords were treated like fashion accessories, even like toys. The mighty fantasy hero would hold his sword pointing up at a stormy sky like a medieval lightning conductor. If he wasn’t actually saying, “I have the power!,” then he might as well have been. Or he’d be using the sword in play-duels with feisty ladies, or in highly theatrical fights that’d go on for hours, with lots of time for leaping on tables and urbane baddie-baiting banter. Very occasionally, the sword might go into someone, or separate body parts with a drop or two of blood. But otherwise, such swords had no more menace than a cardboard prop wielded by a rookie cosplayer at his first anime convention.

Need we say that the swords in Berserk are different?

They don’t have any functions as toys, or fashion accessories, or aphrodisiacs. Nope – they’re bloody huge lumps of metal, created for the single purpose of turning the enemy into crimson-coloured chutney. One of the main set-pieces in the second Berserk film, The Battle for Doldrey, has the hero Guts taking on around a hundred warriors single-handed, carving through them like a chef preparing a bumper Sunday roast. You can almost believe it because of how solid Guts’s weapon feels, in contrast to the human blood-bags it dispatches. Later, in the title battle for Doldrey, there’s a delirious moment where a mighty general’s whirling axe causes several horsemen to explode around him.

The film is the second cinema instalment of Kentaro Miura’s Berserk manga, specifically the “Golden Age Arc” centred round the young Guts, his commander Griffith and his woman comrade-in-arms Casca. Berserk newbies should start with the first film, The Egg of the King, though if you know the manga or the 1997 TV anime, then you can pick up here if you want. In The Egg of the King, Guts’s devotion to Griffith led him into an act which shocked even the mercenary; he accidentally killed a helpless child during an assassination mission. Afterwards, Guts was devastated to overhear Griffith declare his contempt for his loyal followers (including, by implication, Guts himself), whom Griffith saw as tools rather than friends.

The Battle for Doldrey divides into three parts. The first relates Guts’s and Casca’s struggle for survival when Casca falls from a cliff in battle and Guts dives after her. In their subsequent adventure together, both characters learn more about each other. The title conflict follows, as Griffith leads his Band of the Hawk against a fortified stone city and a force many times greater. In the film’s last act, the tensions between the characters cause a chain reaction leading to catastrophe.

Doldrey is a more satisfying watch than the first film. Storywise, there’s more character development, including a very pungent, adult sequence where a naked couple are intimately entwined, while the thoughts of one of them are filled obsessively with someone who’s no longer there. It’s a terrific piece of anime drama, animated and edited with great skill, in a film that’s even better-looking than its predecessor. Images like the wounded Casca lying on a riverbank in the pouring rain, or a snowfield in the rising sun, have an unadulterated beauty in the hyperreal, artificial rendering of Studio 4°C.

The Egg of the King sometimes overreached itself in its ambition to show staggering battle spectacles, leading to clunky mixes of CGI and trad animation. In the sequel, it feels much less of a problem, though that may be partly because the fights themselves are more exciting, with the enemies properly introduced before the deathmatches start. Fans of the TV Berserk will be especially gratified to see the return of Adon, Berserk’s closest thing to a pantomime villain. He boasts amusingly ad nauseam of his family’s centuries’-old battle skills which inevitably turn out to be duds, like the Acme gadgets used by the coyote in the Road Runner cartoons. As with Game of Thrones, Doldrey is a wholly human drama, excepting a tiny Tinker Bell-ish cameo at the end.

But it’s also the drama that’s the issue. It should be stronger, and of course it was stronger in other versions of the story. Doldrey seems to presume its audience knows Berserk already. In the middle of the film, there’s a beautifully designed, but weirdly fumbled, encounter between Griffith and the ruler of Doldrey. It hints at a backstory in the manga and TV versions that’s crucial to understanding what unites Guts, Griffith and Casca – basically, pain and rape – but quite honestly, it should have been spelled out here, brought to the forefront. Again, the TV version of Berserk brilliantly presented the growing tenderness between Casca and Guts, in low-key scenes that wouldn’t have eaten the movie’s effects budget. Instead, the film gives us an extended ballroom dance that’s pretty but romcom cheesy.

Without strong connective tissue, Doldrey feels like a middle, a middle and a middle. The focus shifts awkwardly from Guts and Casca to Guts and Griffith, but it lacks a powerful sense of these characters as a triangle, playing out a destiny that – whatever each of them may think – is shared and melded in concert. Without that, we’re left with a film that shows what cinema anime can do – magnificent images, hypnotically timed set-pieces – but also reminds us of what it often misses – the hearts of its characters and their intersecting relationships, gained through many episodes’ worth of acquaintance.

(My review of the third Berserk film, The Advent, was also published in Neo magazine.)

It’s easy to point out what’s wrong and unsatisfying about the Berserk films, whose faults often reflect the shortening of the source material. Consequently, the films will probably always be undervalued by fan pundits, though this last part strives heroically – and there’s something genuinely heroic about Advent – to lift the trilogy to greatness.

The Advent starts like Return of the Jedi, with Guts and Casca freeing their imprisoned leader Griffith, the man they love and honour. But instead of Ewoks, the story goes on to mutilation, madness and Armageddon, for the characters if not their world. Rage, pity, despair and vengeful madness converge into sublime hysteria, as landscapes turn into lakes of blood and mountains of heads. The film has caught flak for its demonic sexuality, which can’t help but recall Overfiend. Yet it’s playing out a dark fantasy as old as Dracula, a sacrificial rape where the victim desperately desires her rapist. (It’s balanced, Irreversible-style, by a delicately-played consensual love scene.)

The film has more of an ending than the TV version, but doesn’t pretend to complete the story, which hasn’t finished in manga form. Beyond Guts, Griffith and Casca, the other characters are vague sketches (or hyperlinks to longer versions of Berserk), overshadowed by a deus ex machina warrior with a few scant lines of backstory. Yet within its limits,Advent throbs with power.