(Sight & Sound, BFI)

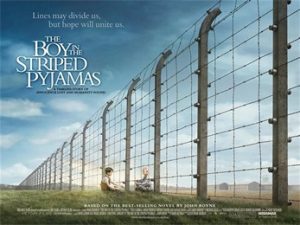

Berlin, the 1940s. Eight year-old Bruno is the son of a German officer. Bruno’s father is promoted and takes his family to a forbidding country house staffed by soldiers. Bruno, a dreamer who loves adventure books, is intrigued by what he thinks is a nearby farm, whose inmates wear striped pyjama-like clothes.

(This review reveals some details about the end of the film.) In The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas, a little boy travels with his family to a mysterious, forbidding stone house in the countryside. The boy, who loves adventure stories, explores the sunny woods around his new home, ignoring his parents’ cautions. Finally, he comes upon a place of dark secrets, meeting another boy who’s imprisoned there. They become friends, though the barbed-wire fence between them is a reminder of the threatening adult world.

Of course, any grown-up is amply forewarned that this story is a device, a fairytale illusion. The setting of the film is wartime Germany; we know what the striped “pyjamas” of the captive child mean; and we know what the place in the woods really is. This isn’t a children’s film in any conventional sense, though it’s clearly been made with children in mind. (The film has been rated ‘12A,’ which seems wholly appropriate.) It’s hard to predict how it will fare in cinema, but its long-term home will surely be the classroom, where it may well become a standard teaching tool.

For grown-ups, The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas is harrowing, but so strange to watch that one can feel distanced from it; it’s the film equivalent of a beautifully-tended minefield. It starts with tinkling pianos, rosy-cheeked children, handsome period detail, familiar (mostly British) faces and the textural reassurances of a Hollywood heritage piece. But mixed in with all of this are discordant, menacing notes, some subtler than others. The backgrounds are full of swastikas and Nazi troopers; we glimpse the “liquidation” of Jewish homes; and we see children play-shooting each other dead.

The film ends in horror, though there’s a careful balance between what is and isn’t shown. The tragic conclusion is essentially faithful to the acclaimed source book (by Irish author John Boyne), which is frankly a shock in itself. True, the film injects a theatrical build-up of suspense in the last scenes, which could be taken as a moral compromise, but the last shots have the wordless force of a Holocaust museum exhibit.

Directed by Mark Herman (Little Voice, Brassed Off), the well-mounted film shies away from an overtly personal voice or interpretation, except for its overarching device of presenting its characters “like us.” The characters have German names but not German accents. The boys are superbly played by British youngsters; the soulful-eyed Asa Butterfield, briefly seen in this year’s Son of Rambow, plays Bruno, the son of a Nazi officer, while newcomer Jack Scanlon plays the captive Jewish boy Shmuel. The story might have been kept mostly at their level, but Herman opts to counterpoint their friendship with grown-up conflicts, especially the breakdown of Bruno’s mother (Vera Farmiga) after she learns the true nature of her husband’s “patriotic” work.

Bruno’s father is played by David Thewlis, who’s now an established screen patriarch after playing the paternal Professor Lupin in the Harry Potter films. Thewlis presents the concentration camp commander as an often distant father who’s nonetheless capable of showing warmth and kindness to Bruno, before he goes out to discuss the efficiency of crematoria with his men. (Thewlis was inspired by the letters of Rudolf Hoess, the first commandant of Auschwitz.) Early on, the character’s freethinking mother (Sheila Hancock, providing the film’s one adult moral authority) reminds him that he always loved dressing up in uniform, a clever way to suggest banal evil to a young audience.

Bruno himself thinks that the concentration camp is a strange “game” (which he thinks would explain, for example, the numbers on Schmuel’s uniform). At times the whole film feels like a horrible riposte to Robert Benigni’s Life is Beautiful (1997), whose hero told his son exactly the same thing. Then again, The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas contrives its own rules, especially when it lays the groundwork for the film’s shattering conclusion. For example, it slightly stretches belief that Shmuel, who’s plainly suffered in the camp, would be quite so supportive of the bold but disastrous scheme concocted by his friend.

Author John Boyne called his book, “A fable told from the point of view of a naïve child, who couldn’t possibly understand the horrors of what he was caught up in.” It’s fitting that the film is distributed by the Disney studio, which once made a war propaganda cartoon, 1943’s Education for Death, about a German boy whose innocent soul is destroyed as he’s indoctrinated into Nazism. In The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas, Bruno stays innocent but becomes a victim of his own childish unknowing. It’s we, not him, who have a sobering education in death from this brave and powerful film.

[amazon_link asins=’B004UGALMC,1862305277′ template=’ProductCarousel’ store=’anime04c-21′ marketplace=’UK’ link_id=’1dcb5c91-accd-11e8-b94c-3fc3ff656970′]