(SFX Magazine, Future Publishing)

The sign on the soundstage door warns, “Wolves on set.” Within, the fairy-tale forest is darkened. This is a night scene, in which scared peasants are trying to lure one of the predators into a trap. A huge timber wolf stalks the undergrowth, brought to the set not from Transylvania, but from a farm down in Sussex. There are animal handlers lurking nervously behind the fake trees, trying to tempt the beast to walk the right way. This is savage, wild nature, the jaws that bite, the claws that catch…

Quack! It’s a sacrificial duck, which the peasants are using in the scene to lure the beast to its doom. In a flash, the dark lord of the forest turns tail and runs for its life. “It was terrified of the duck!” remembers director Neil Jordan. It’s an anecdote almost as strange as the film itself.

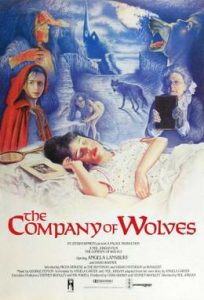

Despite Jordan’s own denials, The Company of Wolves is a landmark horror film. But it’s also an Alice-style dark fantasy, a Freudian feminist fairy-tale, a young lady’s guide to dating werewolves, and an allegory for the sexual awakening of a pubescent girl. Dreaming herself into the world of Red Riding Hood, young Rosaleen hears and tells various stories about wolves, allowing for a wide range of striking fantasy visions. Well-dressed aristos get hairy at a banquet, babies hatch from bird-eggs, and there’s a satanic cameo from Terence Stamp in a Rolls Royce. The film circles round to the best-known wolf tale of all, as the red-cloaked Rosaleen meets a handsome stranger in the woods who is, as her granny would say, hairy on the inside. My, what big teeth you have…

Neil Jordan is a front-rank director now, thanks to The Crying Game and Interview with a Vampire, but The Company of Wolves was only his second film. His debut was Angel – nothing to do with vampires, but a gritty, downbeat crime drama starring Stephen Rea, who would reappear in several Jordan films, including Company of Wolves. Back then, Jordan was arguably more famous for his literary work, having written two novels and a short-story collection.

Jordan was wearing his author’s hat when he went to Dublin in 1982 for a conference celebrating James Joyce’s centenary. Here he met Angela Carter, whose novels dated to the 1960s (including another surreal story of a girl’s coming of age, The Magic Toyshop, filmed in 1987). However, she was most famous for her 1979 story collection, The Bloody Chamber. The stories drew on traditional fairy tales, taking them in unexpected ways to decidedly non-patriarchal resolutions. But Carter bristled when asked if her book was an exercise in feminist revisionism.

In Carter’s words, “My intention was not to do ‘versions’ or, as the American edition of the book said, horribly, ‘adult’ fairy tales, but to extract the latent content from traditional stories.” Among them was Red Riding Hood, which Carter reworked as “The Company of Wolves.” In this brief tale, a young girl finds a werewolf lurking in her granny’s house, but proves more than a match for it.

When Jordan met Carter at Dublin, she’d scripted a radio version of “Company of Wolves,” which Jordan read. “Angela’s message was that behind these saccharine kids’ bedtime stories was real blood, flesh, hair, and a seething torrent of sexuality,” Jordan says. “I had a fascination with fairy tales and understood where she was coming from immediately.”

Much as Philip Pullman would do with Adam and Eve in His Dark Materials, Carter recast a cautionary tale as a liberating fable. The wolf isn’t just a predator, but it symbolises the girl’s burgeoning sexuality, ringed round with repressive warnings and scare-stories. Before The Bloody Chamber, Carter had translated Charles Perrault’s Red Riding Hood, which warned women to protect their chastity: “Children, especially pretty, nicely brought-up ladies, ought never to talk to strangers.” Rosaleen breaks the rules, realizing her womanhood and smashing the walls between dream and reality in a cataclysmic climax. As her mother says, “If there’s a beast in man, it meets its match in women in too.”

Rosaleen’s story couldn’t support the film alone, so Jordan suggested weaving it with other tales and tales-in-tales, inspired by fleeting anecdotes in Carter’s narrative, other stories in The Bloody Chamber, and even Jordan’s own novel, Dream of a Beast (which had the image of a baby hatching from an egg). For two weeks, Jordan and Carter hammered out the script in Carter’s Clapham house. “Every morning we would meet and imagine these extraordinary scenes,” Jordan said. “We had total freedom playing with different genres, multiple meanings and ideas of reality and fantasy. We had a ball.”

Company of Wolves went into production when British studios were hosting enormous fantasy worlds for The Empire Strikes Back, The Dark Crystal (both filmed at Elstree Studios) and Krull (shot at Pinewood). “We had to create an enormous forest out of twelve trees,” Jordan recalled ruefully of his nine-week Shepperton shoot. The responsibility went to production designer Anton Furst, formerly a laser effects pioneer, who had to work with low-tech equipment. “The trees were on big wheels which you’d roll around on wheels to create other environments and paths,” said Jordan. “We wanted every tree to somehow look like feet or hands, everything to be anthropomorphic. We thought of having trees with roots like stiletto heels, but we couldn’t afford it.”

The spectacular wolf transformations were handled by effects artist Christopher Tucker, who had created John Hurt’s makeup for the title role in The Elephant Man. A sinister “traveling man,” played by Stephen Rea, literally tears his own face away. Later, a flamboyantly seductive huntsman, played by the dancer Mischa Bergese, howls in agony, only for a wolf’s muzzle to push out of his jaws. It’s much the same kind of body-horror coup that John Carpenter had recently used to different ends in The Thing.

However, executive producer Stephen Woolley was anxious to distance Company of Wolves from other genre fare. “Horror movies tend to fall into two categories these days,” he argued. “They are either the Friday the 13th type or The Thing type. One is extremely nasty and the other goes overboard with special effects. If you try to straddle these two aspects, as I think (Paul) Schrader’s Cat People did, and aim for an intelligent horror film, you tend to fall between two stools. Whether that is the correct approach or not, it is the approach we are aiming for.”

Company’s cast included such familiar British faces as Brian Glover, Graham Crowden, David Warner (who plays Rosaleen’s father in the real and fantasy worlds) and Angela Lansbury as the girl’s stern grandmother, with a living fox-fur round her neck. The central role of Rosaleen went to 13 year-old newcomer Sarah Patterson, who fitted Jordan’s idea of a bright, unaffected girl, naïve but at the same time preternaturally bold. By an extraordinary coincidence, Patterson came from the same Hampstead school where granny Lansbury studied several decades earlier.

For the cameo role of the Devil, Jordan had been hoping to get Andy Warhol, but when the artist refused to fly to England, Terence Stamp stepped in, taking the role for the price of a new suit. The naked “wolfgirl” who emerges from a well (described by Jordan as Rosaleen’s alter-ego) was played by underground musician Danielle Dax.

The film opened in Leicester Square, but both Jordan and Carter were disappointed that it was given an “18” certificate. As the critic Philip French pointed out in his review, the certificate excluded “the mid-teenagers who would especially understand, enjoy and be enriched by the film.” The average person might think that it was moments such as Rea gorily tearing off his face that led to the restrictive rating. Carter, though, thought it was down to politics. “The Thatcherite censorship found (the film) subtly offensive. They couldn’t put their finger on it, but they knew something was wrong,” she told Marxism Today.

The film was successful in Britain and Europe, though it foundered in America, where, according to Jordan, “They tried to flog it as a down and dirty horror movie.” During the marketing of the film, there was a scary incident on a TV talkshow. Patterson was talking in the studio about playing Rosaleen. Also present was one of the wolves from the film, perhaps the one that had been humiliatingly spooked by the duck. Jordan recalled: “Suddenly the wolf went for Sarah, tried to grab her by the throat. Thank God it was on a leash that they pulled back.”

Jordan, of course, went on to world fame as a director, and is now developing a version of Neil Gaiman’s The Graveyard Book. Other participants in The Company of Wolves have been less fortunate. Carter died from cancer in 1992, aged 51. Anton Furst went on to win an Oscar for designing Gotham City in Tim Burton’s Batman, but he committed suicide shortly afterward. And after her bright start, Patterson faded from view; one of her few subsequent credits was in a straight-to-video Snow White, opposite Diana Rigg.

The Company of Wolves, though, is remembered as a milestone of fantasy cinema, a weird, haunting one-off that feels essentially unlike any other film. Explaining its appeal, Neil Jordan harked back to the spirit of fairy-tales. “You feel like you’re visiting somewhere that you’ve been before, like Hansel and Gretel’s cottage,” he said. “We tried to build each set so that it reminded you of something you had seen, but you weren’t quite sure what it was.” Asked how he would describe his film, Jordan called it “a sensual nightmare.”

Boxout: THE HOWLING

Director Neil Jordan hoped to use real wolves in the film. “There were four wolves that we could track down in the entire British Isles,” he says. “Two of them were in Scotland, and we had them driven down, but on the way one wolf ate the other in the back of the truck.” After that disaster, Jordan used the surviving wolves sparingly, often substituting Alsatians and Malamutes (a Malamute is a cross between an Alsatian and a husky). However, in a climactic scene where the girl puts her arms round a wolf, it’s a real wolf she’s hugging. Brrr.

Boxout: FROM WEREWOLVES TO VAMPIRES

One fan of Company of Wolves was Anne Rice, who describes her vampire heroes Lestat and Louis watching the film repeatedly in her book, Tale of the Body Thief. “Anne said that she wanted me to make Interview with a Vampire because Company of Wolves was Lestat’s favourite movie,” says Jordan. He had already discussed a vampire film with Carter, along the same lines as Company of Wolves. “When I finished The Crying Game, I was going to call (Carter), but she died that year,” said Jordan. “I still have the outline she wrote and would love to return to it one day.”

[amazon_link asins=’B00FFIO2JW,B000ANVNO4′ template=’ProductCarousel’ store=’anime04c-21′ marketplace=’UK’ link_id=’cc960b36-9c67-11e8-ab00-3ffe697a3ef5′]