(Judge Dredd Megazine, Rebellion)

“John Carter of Earth? John Carter of Mars sounds much better.” So the titular hero of the planetary-romance screen blockbuster John Carter renounces his birthworld and homo sapiens peers, as Sam Worthington did when he went native on Pandora three years ago. Carter and Avatar’s Jake Sully have gone beyond striking poses on our boring, mundane world, like superheroes or Matrix warriors. Rather they dismiss our world, and find themselves another.

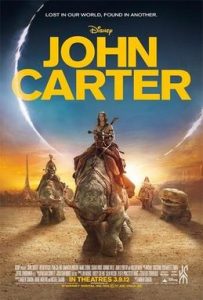

In the 1940 novel Slan by A.E. van Vogt – which inspired the geek slogan, “Fans are Slan!” – the new-style humans were psychic and superintelligent. John Carter, as one adversary notes wryly in the new film, is not so endowed. But he can leap great distances in a bound, like the earliest Superman. He also has a pretty face, a Charles Atlas torso, and a background in the American Civil War. His story is a period fantasy, based on a pulp-magazine serial called “Under the Moons of Mars,” better known by its book title, A Princess of Mars. It was written by Edgar Rice Burroughs, who debuted Tarzan in the same year; 1912, a century ago.

John Carter’s director Andrew Stanton is demonstrably given to retro – this is the man who directed Wall-E, about a Chaplinesque robot taught love by Hello Dolly! showtunes. So John Carter isn’t reimagined, as in Avatar; he’s still Burroughs’s former confederate soldier from the nineteenth century. Mars is similarly old-fashioned. The mayfly-winged alien vessels may be solar-powered, but they’re armed with giant cog-shaped cannons, akin to Jules Verne more than George Lucas. The desert scenery and scanty costumes are unadorned Oriental fantasy. Utah doubles as Burroughs’ dried-up Mars of mesas, gorges and scrubby plains, though some Earth scenes (including Carter’s mansion) were shot in South England.

The film wants to be a straightforward hero’s swashbuckling journey, though it trips itself up with explanations and complications. It needs the spontaneity of Wall-E, which began with a breezy Michael Crawford proclaiming “Put on your Sunday clothes.” But John Carter opens with a portentous voiceover; even some Holst would have been a more fun way to introduce Mars. The film has three framing prologues – one with a bemused junior Edgar Rice Burroughs – before Carter (Taylor Kitsch) is chased by irate Apaches and military into an Arizona cave, where he’s attacked by a stranger with searing blue eyes and zapped to Mars, which bulges with alien factions and difficult names demanding a fannish mindset to remember. There are Heliumites (human-like, red tattoos), who fight the Zodangans (human-like, blue tattoos), who are manipulated by the Therns (nominally human-like demi-gods, with the eyes). There are also Tharks (insectile four-armed green beansprouts), who are created in CGI and capture Carter on arrival.

As in Avatar, the hero falls under the care of a maternal giant (Samantha Morton) who treats him as an infant to be pummelled into maturity. There’s some effective grotesquerie involving the Thark’s own hatchlings, mewling clingy hobgoblins which feel closer to a David Lynch nightmare than to a chuckling Pixar babe; and the film makes a “grittier-than-Pixar” statement by showing the Tharks destroying eggs which hatch too late (though Stanton’s Finding Nemo also had a mass infanticide). To balance the seriousness, Carter is shown as a superpowered stumblebum, struggling to cope with Mars’s trampoline gravity, or getting slapped on the head for leading an army the wrong way. Stanton also introduces a Martian bulldog which slobbers and licks its way through the picture, racing round the desert at cartoonishly high speeds. It sounds appalling, yet its doggy buoyance strikes a better note than most of the script.

“Rubbish!” exclaims the feisty princess heroine (Lynn Collins) at her own opening speech, which is cute, but the leather-clad natives’ dialogue still feels like stretched TV camp. In Avatar, even the dreadful dialogue drove the action. In John Carter, it’s just in the way, and even the theoretically important plot points only half-register, like Mars’s lack of oceans. Visually, Avatar was much more evocative, introducing its aliens in a stunning Peter Pan nightscape. John Carter goes for desert dust and grit, but it can’t sustain an atmosphere that’s pungent or special. The “harsh” moments bump out of place: a mid-film crescendo sees Carter on a berserk Martian killing spree while burying his Earth family in memory, which is forceful yet pointless, as the derring-do resumes afterward unchanged.

Later, there’s a odd moment where Morton’s character, who’s supposedly the most compassionate of her species, readily kills a female rival. It may have been meant to shock, but the viewer’s main response is, “Well, that monkey needed to rip up someone.” Considering this is a film by a Pixar director, the Tharks are extraordinarily unmoving and TV-cartoonish. We learn in the end credits that their performances were “captured” from thespians like Morton and Willem Dafoe, but that’s never reflected in their ineffectual faces, already blown away by Andy Serkis’s Caesar and the tigerish Zoe Saldanha in Avatar (yes, bloody Avatar).

There’s no real effort to clarify what the different Martian factions are about, which makes the story mildly confusing and deeply hazy. Seldom do we learn why anything matters. The Earth scenes don’t matter; Carter could have been dropped on Mars after two minutes, as the gumf about gold-mines, cavalry, Apaches and excavations falls into irrelevance. On Mars, the plot turns opaque, like a Star Wars prequel if you don’t know what’s coming. Hidden beings hide the secrets of “ninth rays” and “feed” off history, an occult activity that involves Mark Strong’s evil angel setting up shotgun royal weddings and playing Basil Exposition to a hostile hero (though the exposition scene is one of the film’s most pleasurable, backdropped by an epic swirl of human crowds and alien machinery). The fan viewer is meant to be thrilled by the implicit promise of sequels to pay everything off. The non-fan summer audience is treated like the giant Martian bulldog, asked to enjoy the runaround and not worry about what it’s for.

(c) 2018 Rebellion A/S. Reprinted with permission.