(Judge Dredd Megazine, Rebellion)

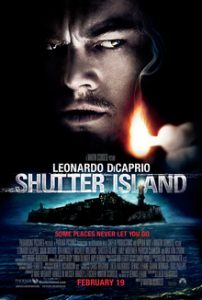

There’s plenty of enjoyment, if less true weight, in Shutter Island, the new mystery-melodrama from Martin Scorsese, teamed up once more with star Leonardo DiCaprio. The story is based on the book by Dennis Lehane; the year is 1954 and DiCaprio is Teddy Daniels, a US marshal arriving at the titular stormy island where a hospital houses the criminally insane. Our first sight of DiCaprio is of our stubbly and shop-soiled hero heaving with nerves and seasickness on the boat to the island across Boston Harbour. It briefly took me back to the actor’s neurotic Howard Hughes in a previous Scorsese film, 2004’s The Aviator. On Shutter Island, though, we’ll find out what really makes Teddy tick.

Teddy and his new partner, Chuck (Mark Ruffalo), investigate a missing prisoner, Rachel Solando, who was put away for killing her children. Presiding over the hospital is the genial (and therefore highly suspect) Dr. Cawley, played by Ben Kingsley. Rachel’s own doctor is strangely absent, but Teddy does encounter Cawley’s even more suspect German colleague, Dr Naehring, played by the one and only Max von Sydow. Naehring reminds Teddy of his terrible war experiences, and flashbacks and dreams pile in. The dreams are lengthy and lurid, sometimes not far removed from last month’s The Lovely Bones, as Teddy painfully envisions his dead wife (Michelle Williams).

That’s probably about as far we should go with the précis. Of course there are hidden agendas and secret histories, taking us a long way from the initial mystery of Rachel’s escape, though it plants the clues to what’s really going on. Meanwhile, we’re shown Teddy suffering from migraines and taking medication from Cawley, prompting doubts about if everything he sees is real (wait till you get to the rats!), or if Scorcese is playing unreliable narrator.

Some of the film’s artificial devices are jokily melodramatic, such as the brassy overwrought score that rises to a mad crescendo as Teddy and Chuck arrive at the asylum’s gates for the first time (if only Bernard Herrmann was still around!). Max von Sydow, looking as solid as Boris Karloff did in his Frankenstein days, is introduced in a velvet armchair, swinging round from a roaring log fire like a Teutonic Bond heavy. Later in the film, a torrential hurricane screams around our heroes; it’s as much a part of Scorsese’s amusement park ride as the damp dark stone passages, ringing with the screams of madmen, like the asylum-dungeon Silence of the Lambs bits revved up to eleven.

It’s very easy to enjoy being in the film, harder to know quite what to make of it. Many viewers will spot “the” twist long before it’s revealed; it’s one we’ve seen before, long absorbed into the DNA of mystery thrillers. I’m in the minority who thinks Shyalaman’s The Village still holds up on second or third viewing, and any Hitchcock buff knows the twist is often a diversion from the real point. But there doesn’t seem to be much of a point to Shutter Island, beyond the expected technical virtuosity. While some people have compared the film to Kubrick’s The Shining, I was more reminded of Stephen King’s infamous description of that film: a great big beautiful Cadillac with no motor inside. (Actually, Dr. Cawley in Shutter Island has a big beautiful car, and its fate is the funniest part of the film.)

Perhaps it’s all meant as a playful homage to genre thrillers, and certainly other reviewers have been playing “Spot the reference” with Hollywood classics, though I was more struck by Shutter Island’s parallels with the British ghost-story Don’t Look Now. But then Scorsese goes way past the knowing-cinephile comfort zones, including prominent flashbacks to Teddy as a World War II soldier among the liberators of a Nazi death camp. The full-on Schindler’s List imagery suggests that either Scorsese believes his hokey story has a genuine moral weight, or else that his vision of legitimate popcorn cinema is now several orders more outrageous than Tarantino. Old Alfred Hitchcock, to name one of Scorsese’s heroes, never needed to bolt Holocaust imagery onto his thrillers to make them spiritually profound; and Shutter Island is, frankly, more spookhouse than Psycho.

(c) 2018 Rebellion A/S. Reprinted with permission.