(SFX, Future Publishing)

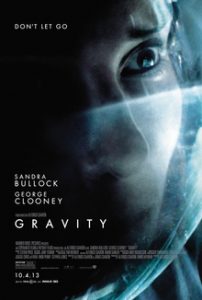

In space, no-one should be able to hear other people eating popcorn, or slurping soda, or locking lips with one another. For all these reasons, watching Gravity at home has advantages, removing the multiplex audience who can’t bear silence without pouring their own noise in to fill the vacuum. It reflects the strange kind of film that Gravity is. It has one foot in mainstream multiplex Hollywood, starstruck with the silky tones and beautiful blue (sorry, brown) eyes of George Clooney; and another foot in the arty sphere of 2001 and Solaris.

Gravity is a really beautiful film, and a terribly convincing beauty, as opposed to fantasies like Pandora. If we’re somehow able to go into outer space and find that it doesn’t look like Gravity, we’ll ask for a refund on our rocket tickets. It looks especially good on the 3D Blu-ray. The spacesuited figures bump and spiral through endless undulating shots, with much of the reach-out-and-touch-them realism they had in cinema. But so much of Gravity’s majesty depends on the Earth, on the clouds, continents and oceans which serve as the ultimate in background props. You need a big screen to bask in the global detail. Too small and it can look like a painting, while the characters occasionally have a cut-out look in 3D when they’re not in the foreground. But we’re nitpicking.

The film improves on repeat viewing. Yes, the story of two astronauts (Sandra Bullock and Clooney), struggling to survive when their craft is struck by orbiting debris, is a schematic cliffhanger yarn, a Perils of Pauline in CGI spacesuits. You can practically feel the director one step ahead, igniting the next space station fire or draining the next fuel cell, the filmmaker as malign God. The script’s invocation of faith annoyed some viewers, but it dramatically fits a film whose characters spend much of their time speaking into dead-seeming microphones which just might be heard by NASA Ground Control, like prayers through the void

Gravity doesn’t just use cliffhangers, it redefines them. So much of the action is about the desperate need to catch onto something, anything, with characters scrabbling frantically about the outsides of spaceships, grabbing rungs, yo-yoing on tethers – or, the awful alternative, being hurled headlong into the void. Perspectives are reversed. In the brilliantly-studded pit of space, Earth has become the great beyond. In a haunting scene, Bullock tunes into voices from Earth: a man, a dog, and – heartbreaking for her – a baby. She doesn’t speak their language, but howls along with them as representatives of the life, all life, that she’s lost, music for her lonely funeral. In this scene at least, the film connects with its artier, non-Hollywood precursors, especially Ray Bradbury’s 1949 (!) story “Kaleidoscope,” a far darker take on the same theme.

Of course, Gravity is full of Hollywood-isms, especially the way it makes Clooney the man of Bullock’s dreams in a rug-pulling practical joke, and gives Bullock a character arc of Heroine’s Journey 101. It’s notable though, that there’s an obvious place where the film could end, triumphantly but ambiguously, with Bullock’s brave speech that she may live or die but “Either way it’ll be one helluva ride.” Maybe Cuaron is inviting us to make our own Viewers’ Cut if we don’t like his version of the film. After all, this is one of the most amazingly immersive movies ever made, even on the small screen.

[amazon_link asins=’B00IHRZOC2′ template=’ProductGrid’ store=’anime04c-21′ marketplace=’UK’ link_id=’21e57f64-1221-11e9-ad62-3fec4401f29c’]