(Sight & Sound, BFI)

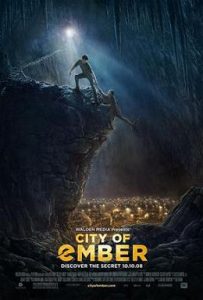

Following The Truman Show (1998), The Matrix (1999) and The Village (2004), City of Ember returns to Plato’s fable of the cave, his allegory for how humans are sealed within a deceptive, false reality. Gil Kenan’s film is an especially tight fit to Plato’s story. Its protagonists live underground in a gigantic cavern after some global disaster, with no concept of the sun, mistaking their web of faltering electric lights for true illumination. As this is a children’s film, two plucky youngsters (Saoirse Ronan from last year’s Atonement and a ten-years-older Harry Treadaway from 2005’s Brothers of the Head) must penetrate the veil.

City of Ember is based on a low-key, rather sombre debut book by American author Jeanne DuPrau, which focused on themes and characters more than action. In particular, Duprau highlighted the fallibility of her preteen protagonists, who make naïve mistakes and are subject to pride, greed and selfishness. DuPrau also tied in some contemporary issues, such as the blithe assumption that our world has abundant energy and resources.

However, her book could really only support about half a film. (DuPrau expanded her story in three follow-ups.) The film throws in new material, including a man-eating monster mole, a patriarchal backstory in which the kids realise they’re following a trail blazed by their fathers decades before, and a modestly explosive climax involving a bursting dam.

Unfortunately, the action feels tinny and TV-sized. The patchwork city of Ember looks small and stagey, with little mood or atmosphere. When its secrets are revealed at the climax, Ember turns into an unsafe theme park, complete with its own automated log-flume. Even the supposedly terrifying blackouts aren’t properly dark; the city’s inhabitants shoot up flare lights, which they didn’t have in the book.

Like the violent The Mutant Chronicles, which opened in Britain in the same week as City of Ember, the designers have gone for a retro-future “steampunk” look, with Heath Robinson machinery (one glimpsed robot looks like Wall-E) and subterranean steam-driven technology. At times, the film evokes the fantasies of Terry Gilliam, Marc Caro and Jean-Pierre Jeunet. The most impressive sight is the towering generator powering the city, recalling the Steam Tower in Katsuhiro Otomo’s animated Steamboy (2004). However, the candy-coloured sets are also reminiscent of cheesier children’s fare from yesteryear, such as Daleks: Invasion Earth 2150 AD (1966).

As in such films, the acting tends towards the fruity and irritating. Mackenzie Crook leers as an obvious ne’er-do-well, singer Mary Kay Place plays a happy-clappy evangelist, and Bill Murray simpers in a padded suit as the city’s greedy Mayor, whose funniest moment is when he meets his comeuppance. Tim Robbins is glum as the boy’s inventor father, but gravitas is clearly not what Gil Kenan was aiming for. As the book’s themes and revelations are muffled, made nonsense, or given away in the pre-titles prologue, more underground monsters could have compensated. A film called Monster Moles could have been a nice companion piece to Kenan’s CGI debut, Monster House (2006).

[amazon_link asins=’0552552380,B001LNW2IS’ template=’ProductCarousel’ store=’anime04c-21′ marketplace=’UK’ link_id=’b1abae80-c844-11e8-af14-6757a6ffb500′]