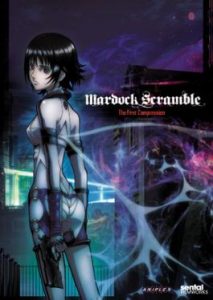

(I reviewed the first Mardock Scramble film in Neo magazine, Uncooked Media, below. My reviews of the second and third films are linked underneath.)

In a future New York where cars drive on air and technology resembles magic, a wretched fifteen year-old girl’s life comes to a terrible end – only for her to return from the dead as a bloody avenger. Rune Balot, abuse victim and child prostitute, falls victim to her sugar daddy, the psychopath and money-launderer Shell-Septinos. Then she awakes to find herself remade by a scientist, with telekinetic powers and the chance to kill… and kill… and kill.

When Redline was released, some fans saw the film as an return to outrageous anime, to the kind of work that got anime noticed in Britain twenty years ago. No more moe cuteness, no more Ghibli charm, no more mostly bloodless hero’s journeys. No, we’re talking anime that ordinary, non-fan viewers wouldn’t watch comfortably. Instead, they’d say “What the heck is this?” and bail out. Redline was loud and brash and it pummelled the eyeballs, but it didn’t have the sex, gore and nastiness that made anime headline news in ‘90s Britain, when the Daily Star demanded “Snuff Out These Sick Cartoons!” Step forward, Mardock Scramble.

It’s an anime that features rape, incest, serial killer hordes, and livid violence dealt out by psychos and avengers alike. Mardock Scramble is released just as mainstream pop-culture has caught up in Britain. You can find all the above elements in the recent film, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo. Both films are sexy action-thrillers whose attractive heroines undergo sickening horrors, which some viewers will find just sick. Anime has been drawn to this twilight territory for decades. Older fans will think of Overfiend, Kite and the original Ninja Scroll.

More prosaically, Mardock Scramble is a hero origin story, with loud echoes of Ghost in the Shell. The luckless girl prostitute Balot is fried alive in a car explosion, then reborn naked in a vat of liquid, to be greeted by a Frankenstein-style scientist, Doctor Easter. (His scariest line: “With 800 corpses to fiddle with, I’m like a kid in a candy store!”) In her new state, Balot can manipulate machinery, screw with traffic lights, possess people’s voices and even shoot bullets from the air.

The talking mouse is a bigger surprise, especially when it turns into a gun. It’s an experiment called Oeufcoque, and it’s a caring, wise guardian to Balot, his grave voice only making him cuter. Forget Stuart Little comparisons. Oeufcoque is oddly reminiscent of the talking car KITT in the old TV show, Knight Rider; you could also compare him to the shapeshifting animal “daemons” that complement the human characters in the novels by Philip Pullman. Balot loves Oeufcoque because he’s masculine yet non-sexual; it’s a common mix in anime, but cleverly worked out here. (There’s a particularly poignant scene where Oeufcoque is mortified because Balot picked him up by his tail.)

Doctor Easter is less interesting, at least in the first film. So far we only have a fuzzy idea of how he operates, and who he answers to. Unlike many SF anime, Mardock Scramble isn’t into teams or command structures; the emphasis is squarely on Balot’s alienation from society. The story includes a very uncomfortable trial sequence, in which Balot confronts Shell-Septinos and is interrogated on her own past history. Whatever you think about rape trials in Britain, you’ll be shocked by the attitudes in this sequence, with lawyers openly blaming Balot for the ordeals she suffered as a child.

The author Ubataka says he’s out to criticise Japan’s attitudes to women, though not everyone will agree. The script goes out of its way to engage with misogyny, with Balot even accusing Doctor Easter of raping her (we’re a long way from Astro Boy). Balot also reflects on the hypocrisies of male views of prostitutes; when asked by a patronising policeman which “lucky fella” took her virginity, she says flatly that it was her father, adding, “Don’t you ever think about touching your daughter?” She makes other confrontational comments, rarely heard from anime girls (“You men are always saying you know you wanted it too.”) But the pictures undermine the script. Balot is frequently shown nude – sometimes tastefully, sometimes luridly – or wearing thigh-flashing outfits while she trips back to past rapes.

As with Mardock’s anime predecessors (Ninja Scroll et al), you have to accept these queasy contradictions as a package, or not at all. The uncomfortable themes, though, put an interesting new focus on old SF tropes. The killer Shell-Septinos has his memories wiped clean after each new rape-killing, so that sex for him is literally a petite-mort and double suicide. The manipulation of memory has been in cyberpunk ever since Blade Runner. In Mardock Scramble, though, it’s given a heartbreaking extra twist: the tortured Balot would do anything to be rid of her memories.

Actionwise, the bangs and crashes are mostly kept back for the last ten minutes, but believe us, it’s an impressive finale, drenched with old-school gruesome details (Severed fingers! Bleeding guns!). The art, by the previously second-string GoHands studio, is solid and well-composed with moody blue-green palettes, though the quality drops out in a badly-edited car chase featuring vehicles out of a Sega game. The character animation is bland, but the Japanese voices and music are both excellent. Balot has the voice of Megumi Hayashibara, famed as Rei in Evangelion, who once declared that, “I am not your doll.” The next two Mardock Scramble episodes will tell if Balot can grow past the gunplay and fetish outfits.

(My review of the second Mardock Scramble film, and my review of the third, are both available on the Neo magazine website. I also wrote a piece on the manga version of Mardock Scramble – drawn by Yoshitoki Oima, who went on to create A Silent Voice – for the MangaUK website.)

[amazon_link asins=’1935429531′ template=’ProductAd’ store=’anime04c-21′ marketplace=’UK’ link_id=’fbaa74e1-accf-11e8-b3c5-b510a5666b3f’]