(Sight & Sound, BFI)

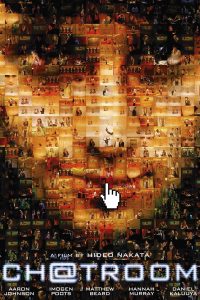

The recent The Social Network showed how online communities can express dysfunctional, destructive and self-destructive personalities. Chatroom takes on the same theme, but in a manner that could be kindly called eccentric, and few viewers will be so kind. Although Chatroom aims to be a disturbing thriller, it misses out what could have been its big twist. If only it could have left its director’s name a secret until the end titles! For this stagy, low-budget British melodrama, largely revolving around London’s Camden Lock and a very low-rent vision of cyberspace, was made by Hideo Nakata, the world-famous director of the Japanese horror film Ringu (1998).

Chatroom is an old-school Awful Social Warning, in which several strangers meet in an online chatroom to be manipulated in increasingly dastardly ways by the room’s seductive sociopath founder (Aaron Johnson). One of the film’s central devices is to visualise the internet not as some Tron-like neon aether but rather as a peeling, putrescent green corridor with websites as virtual “rooms,” in which strangers chat, party, have tacky sex in curtained closets or mob the weak to suicude. Unsurprisingly, Chatroom was based on a stage play (by Hunger’s Enda Walsh), but it’s possible to imagine the crude metaphor working on screen in the hands of, for example, Michel Gondry.

Nakata, though, flubs the film comprehensively. While the internet metaphor takes a great deal of swallowing, it’s the characters who would be laughed off-stage in an am-dram performance. One is quickly reduced to wondering which note rings the wrongest; perhaps the cringingly facile caricature of JK Rowling as the villain’s ruffled upper-crust mother (Megan Dodds), or the poor little posh supermodel character (Imogen Poots) who falls for his bad-lad charms. The dialogue, much of it about generation gaps as seen from the perspective of spoiled whiney youngsters, is painfully tinny and earnestly overamped. Nakata’s drama of false perceptions never feels real, though the attractive young cast try gamely for callow enthusiasm, and are largely excused by their material.

The internet metaphor falls apart fast; why do all the characters appear more or less the same online as they do when they finally meet in real life? In the year of Inception, we constantly expect the ostensibly “real” world in the film to be deconstructed into another net fantasy, but that option is unexplored. There are few obvious signs of Nakata’s involvement, other than a functional atonal score by Ringu’s composer Kenji Kawai, a brief image of a Japanese girl killing herself on webcam, and an increasing emphasis in the film on “forbidden” images. (There was a much-reported wave of internet suicide clubs in Japan a few years ago, as brilliantly dramatised in a macabre episode of Satoshi Kon’s TV anime, Paranoia Agent.)

Nakata’s Vertigo-style 1999 thriller Chaos was built mostly from implausible twists, suggesting a wish to wrongfoot audiences who knew him for Ringu. Perhaps that’s the best explanation as to why he turned to Chatroom. Lovers of transnational curios may find its inept earnestness strangely enjoyable; the same goes for fans of magic-realist British oddballs, such as this year’s superior Heartless. However, as with other net thrillers such as 2005’s Cry_Wolf, Chatroom is far duller than many real-life online stories (Nakata himself cites some horrific cases in the press notes). The British one to beat is still that of a 14 year-old schoolboy who, in the words of the Belfast Telegraph, “posed as a female secret service spy in an internet chatroom to try to persuade a friend to murder him.”

[amazon_link asins=’B00ESZPPJO,B004G7FDKK,B0052Y6U8A’ template=’ProductGrid’ store=’anime04c-21′ marketplace=’UK’ link_id=’d621ff1c-1226-11e9-9112-9fe880c8c94c’]