(SFX Magazine, Future Publishing) “You haven’t gone forward, Herbert, you’ve gone back… You, with your absurd notions of a perfect and harmonious society. It’s drivel. The world has caught up with me and surpassed me. Ninety years ago, I was a freak; today I’m an amateur. The future isn’t what you thought; it’s what I am.”

So declares history’s most infamous (though eloquent) serial killer, Jack the Ripper, to science-fiction author H.G. Wells. At this point in Time After Time, the two legends are sitting in a hotel room in 1979 San Francisco – the future for these Victorians – and watching the world’s horrors on TV.

It’s an anti-Star Trek lesson, about humanity’s inability to escape its violent heritage. Fittingly, both characters are played by future Trek villains. Jack the Ripper is played by David Warner, who would torture Picard in Next Gen (“How many lights do you see?”). H.G. Wells is played by fellow Brit Malcolm McDowell, who’d kibosh Kirk in Star Trek: Generations.

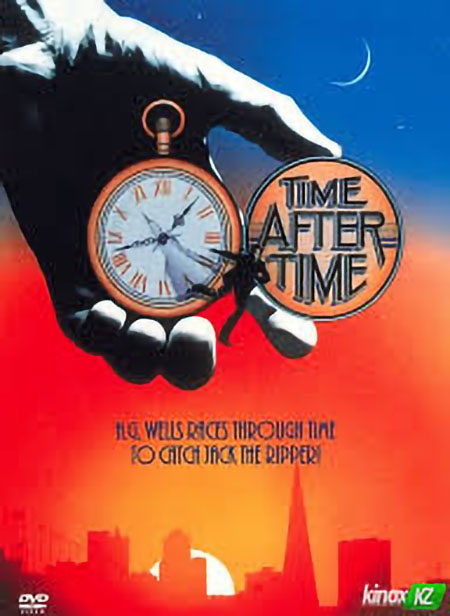

Time After Time doesn’t start in San Francisco, but in the London of 1893. It’s dank and foggy, but McDowell’s youthful Wells is an optimist. He fervently believes the world will become a rational utopia of world peace and brotherly love. In fact, Wells is so convinced of this that he builds his own time machine (a charming steampunk capsule that looks like a mini-submarine) in the cellar of his house.

Summoning his gentleman friends to a farewell supper, Wells announces his departure, but there’s an interruption. Police arrive, announcing there’s been a murder nearby by Jack the Ripper. To Wells’ astonishment, damning evidence is found in the briefcase of one of his guests, Wells’ friend and chess-playing rival Doctor John Stevenson (played by Warner).

Stevenson seems to have vanished from the scene, till Wells has a dreadful thought. Sure enough, his time machine has vanished from his cellar, and Wells realises he’s let the Ripper loose on the future, on the utopia of his dreams.

However, the machine rematerializes, empty (Wells has built it so that it will always make a return trip, except when a special key is used). Girding his loins, the shy author embarks on his pursuit of the Ripper, but he’ll find that 1979 isn’t the utopia that he expected. At least San Francisco’s sunnier than London…

Time After Time was released amid the ‘70s wave of SF/fantasy blockbusters: Star Wars, Close Encounters, Superman. But Warner didn’t think of Time After Time as a science-fiction film. “I saw it as a romantic thriller, with slight science fiction connections,” he tells SFX.

Warner adds, “Some years later I met Robert Zemeckis (Back to the Future) who said Time After Time was his second favourite time travel movie! I believe at the time it was marketed as a romantic film, which perhaps didn’t reflect its mix of genres.” Zemeckis would borrow one of Time After Time’s actors to up the romance in Back to the Future; we’ll get to her later.

Two of Time After Time’s tricks were to reinvent a classic story – Wells’ 1895 novella The Time Machine – and to blur fact and fiction, conflating the real Wells with his own nameless hero. (In the original book, the protagonist is called the “Time Traveller” and he travels not to the twentieth century, but the eight-thousandth century and beyond.)

Time After Time’s director, Nicholas Meyer, had already used such story tricks in a bestselling novel that wasn’t SF. Called The-Seven-Per-Cent Solution, it imagined what if Sherlock Holmes was psycho-analysed by Freud. Published in 1974, the book was filmed two years later (directed by Herbert Ross).

Then Meyer received a phone call from an old university acquaintance, Karl Alexander. He was writing a story about H.G. Wells and Jack the Ripper, influenced by the approach of Seven-Per-Cent Solution. Meyer read the early pages and an outline, and swiftly optioned it as a film.

To complicate matters, Alexander’s novel had originated as a short story that he co-wrote with another author, Steve Hayes, who has a “story” credit on the film. Thirty years later, Alexander wrote a sequel novel, Jaclyn the Ripper(sic).

No doubt the Ripper angle helped to sell the film. Meyer, though, had little interest in the enigmatic Jack. In a contemporary interview, Meyer said, “As a criminal he was strictly small potatoes compared with Hitler or Idi Amin – which is what he realises, of course, in the film. He was only interesting to me as a symbol of malevolence, of the destructive side of man’s nature.”

From this perspective, the hotel scene – which happens after Wells arrives in 1979 and tracks the Ripper down – is the central scene in Time After Time. According to Meyer, the scene was influenced by his memory of seeing TV reports of the murder of Martin Luther King in 1968, and how even such a tragedy was horribly normalised by crass TV advertising.

“I sat on my bed and was truly appalled by what I was seeing,” Meyer said. “People were screaming, and there was blood, and suddenly all of this was interrupted by someone who says ‘Miami for 25 dollars less.’ It’s preposterous, it’s George Orwell time, it scares the shit out of me.”

Warner thinks the hotel confrontation was a great scene, but for him, “It was the whole script that encouraged me to do the film. The thing I remember most about it was my struggle to remember the lines!”

Warner’s Ripper is no eye-rolling caricature. For most of the film, he’s composed, charismatic, and even perversely dashing. At one point he dons a white disco suit that might have been borrowed from John Travolta; it’s a very long way from foggy Whitechapel.

While Warner has said elsewhere that he’s bored of being thought of as a “villain” actor, we ask how he’d rate the Ripper among his evil roles. “If you insist on ‘rating’ it – I’d say number one,” he tells us. “The whole script was quite superior to any other villain roles I’d played.”

Warner adds, “When I first met Nicholas Meyer and the producer Herb Jaffe, they told me they wanted me to play the part, but Warner Brothers wanted Mick Jagger! Thankfully, somehow Meyer and Jaffe prevailed. Also there was the opportunity to work again with my old friend Malcolm McDowell, who by then was a bit of a star.”

Warner appreciated Meyer’s no-nonsense direction of the actors. “On the first day’s shooting Nicholas Meyer gathered the cast and crew together and said it was his first film, please don’t be afraid to come to him with any suggestions. I don’t remember any talks with Nick about intention, motivation or any of that kind of thing. We just got on and did it.

“There was a good atmosphere on set, and Meyer was easy to work with,” Warner says. Actor and director would work together again on the sixth Star Trek film, The Undiscovered Country.

On the effects side, the time-travel visuals for Wells’ journey to the future have dated – some are reminiscent of vintage Doctor Who titles. However, they’re bolstered by a wonderful soundtrack, a sped-up history of 1893 through to 1979, full of audio “glimpses” of music and world events.

“I thought; how could we do (time-travel) differently because it’s usually so boring,” said Meyer of the scene. “The audience sighs and waits till it’s over. I really wanted to do it differently… Could we turn the theatre into a giant radio set for a minute and a half? And I had the abstract images all going forward, a tunnel type of effect, with the radio sounds of different events in history all going around them.”

But Time After Time is remembered for more than time-travel and its Wells-Ripper duel. It has an enormously charming love story, in which the timelost Wells draws the attention of San Francisco bank staffer Amy, played by Mary Steenburgen. Her performance was a complete surprise for Meyer, who quipped, “I wanted a fast-talking city-chippy and I got a slow-talking kook.”

Steenburgen and McDowell are superb on screen together. The undoubted highlight is a restaurant scene where Steenburgen chatters about modern sexual relationships; meanwhile an astounded Wells, that randy prophet of free love, looks like he’s been dropped into the restaurant scene from When Harry Met Sally.

Of course, it helped that the two actors were hitting it off for real; Steenburgen and McDowell married the next year. Steenburgen would appear in a similar role in the third Back to the Future film, directed by Time After Time fan Robert Zemeckis, where she falls for the time-travelling Doc Brown.

But there’s another famous actor in Time After Time, or rather an actor who would be famous. Look closely at the scene where Wells first arrives in 1979, in a museum exhibit about his own life, and a little boy spots him. The lad is Corey Feldman in his first film role, not suspecting that his future involved Goonies and lost boys. But then, as Time After Time reminds us, the future’s never what we expect.

ILL-FATED REMAKE

In spring 2017, ABC aired a TV remake of Time after Time, taking Wells and the Ripper to contemporary New York and adding its own arc plot, a conspiracy which somehow involves the Ripper called “Project Utopia”. Wells was played by Freddie Stroma (Cormac in the later Potter films) and the Ripper by Josh Bowman. The 12-part series was canned in America after five episodes, though the remaining episodes reportedly aired in Spain and Portugal. Arguably, there’d already been an homage to Time After Time in the 1990s series New Adventures of Superman, with Lois and Clark sometimes helped by a gentlemanly time-travelling H.G. Wells.

RIPPER FOR ALL TIME

Many writers have imagined Jack the Ripper surviving into a new age, as in Psycho author Robert Bloch’s story “Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper” and his 1967 Trek episode, “Wolf in the Fold.” Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell’s grisly graphic novel From Hell includes a hallucinatory sequence where the blood-drenched Ripper, midway through his worst crime, finds himself in a modern office space. Unlike Warner’s Ripper, this Jack doesn’t revel in the future’s violence; instead he’s appalled by the bland, spiritless people of today.“How would I seem to you? Some antique fiend or penny dreadful horror, yet you frighten me!”