(Neo, Uncooked Media)

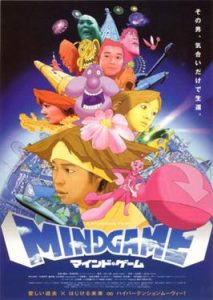

The director Masaaki Yuasa has long been a hero to fans of maverick, free-spirited anime. He’s had a following since his first movie, the extraordinary fantasia Mind Game (2004), which has had one-off screenings over the years (a home release is in the works). More fans discovered Yuasa through his college comedy series The Tatami Galaxy (2010), which was first released in Britain by Beez and later put on Blu-ray by Anime Limited. Yuasa’s next TV hit was the splendid Ping-Pong The Animation (2014), from the sports manga by Taiyo Matsumoto, which was also released in Britain by Anime Limited.

But 2017 may be Yuasa’s annus mirabilis. Somehow he’s found time to complete two cinema anime films, both of which are being shown in Britain just months after their Japanese debuts. One is The Night is Short, Walk on Girl, a madcap midsummer night’s dream in Kyoto. (It’s linked to Tatami Galaxy, though you don’t have to see that first.) Yuasa’s other new film, opening in December, is Lu Over the Wall. It’s a delightful family-friendly fantasy, telling the Ponyo-esque story of a withdrawn teenage boy and a joyous little mermaid.

In the meantime, Neo had the fortune to interview Yuasa when he visited London in September.

Hello Mr Yuasa, thank you very much for speaking to us. 2017 looks like your biggest ever year. Have you enjoyed this year, or have you been too busy to enjoy it?

It’s an anniversary year for me, it’s been thirty years since I started doing animation. I’m genuinely pleased that I have constant work, to be honest. It’s a great pleasure. It’s been hard work but I’m really pleased and happy.

Your early work included animating for two long-running children’s cartoons in Japan: Crayon shin-chan (about a brattish little boy) and Chibi maruko-chan (about a rather nicer little girl). They’re almost unknown in Britain, but you’ve said they were a very creative influence on your style. They seem to have let artists have much more freedom than most other anime would have allowed. How did they allow animation artists to be creative?

They all have really simple animation. Especially with the actions and motions, we could actually play a lot in these series. Because the pictures are quite simple, and easy to draw in a way, you could make it more complicated if you want to, so that’s why it was very creative to work on these animations. From a directing point of view, the stories were based on everyday life, but you could be quite adventurous within that frame, which I think was also interesting.

Many people complain that mainstream, commercial animation endlessly repeats a few artistic styles again and again. In your work, do you sometimes feel that you have to “fight” these mainstream styles in order to tempt people into watching something different?

Actually, I want to make something that can appeal to the mainstream audience. But I want something that I, as a member of the audience, would find fresh but not necessarily drastically different – “That’s new and nice” or “I haven’t seen this for a long time”. That’s what I try for when I make my movies.

Was there a particular work of yours that was a ‘breakthrough’ for you, in terms of commercial popularity?

The Tatami Galaxy, I think.

You use Flash animation software in your recent work. For the benefit of non-animators, can you talk about the effects which Flash makes possible that would be difficult to achieve without it? Is Flash mainly a way of making the animation process faster and cheaper, or does it have deeper artistic benefits?

We use Flash, though the rough animation, the key animation, is done by hand. Flash is really good, because you can create very crisp, beautiful lines, very smooth, and also zoom in and out in 3D. You can maintain original shapes when you expand an image. When I use Flash, I try to keep the hand-drawn feel, and not make it too crisp. You can’t control the drawings as much as you can with hand-drawn animation, but if the animator is really good technically, you can just trust him or her.

Also, Flash makes things kind of compact, so that one animator can work on several different projects; it’s not like conveyer belt work. And also you’re not using pens and pencils with Flash, so your desk is tidy! The software is time and cost-effective.

How would you describe yourself as a director? Some directors have the reputation of being scary, angry people, to drive their staff to make better work. Do you agree with that, or do you have a different approach as director?

I am hardly angry; I am very gentle and kind!

I have read a lot of stories about Hayao Miyazaki’s reputation in the workplace, so that’s why I wondered.

(Laughs) That method might work for some directors, I think, but it just doesn’t work for me. I would create a happy, feelgood environment, so that we work happily, and that gets the best out of the staff, I think.

Do you have time to animate scenes in the works that you direct? For example, did you animate some of the cuts in Lu Over the Wall?

Do you mean key animation?

Yes.

A little, but it’s not so greatly creative; it’s more like following things up. I work on layouts, here and there.

Two of your anime, The Tatami Galaxy and The Night is Short, Walk on Girl, are based on novels by Tomihiko Morimi. (Morimi also wrote the novel The Eccentric Family, which was animated on TV by other hands.) Unfortunately Morimi’s books have not been translated into English. What are their main qualities which appeal to you?

His stories are really unpredictable and fun, but there’s always a solid theme beneath every work of his I read. Also, his use of language is really interesting; that’s difficult to turn into animation, so I express his language in the form of action.

Lu Over the Wall seems more family-friendly than many of your previous works, more ‘gentle’ to the audience. Of course, it still has a lot of wild animation, but it’s not as fast and wild as some of your previous work. Were you making the film as an entry point for people who haven’t seen your films before?

I am hoping for that, yes; I want many people to watch the film.

Lu has a running joke where the girl character, Yuho is frustrated by the boy Kai. when he doesn’t say what she thinks he should say to her (for example, when he doesn’t say “Sorry”.) I wondered if this joke was based on your own observation of people, or whether the idea came from Reiko Yoshida. (Yoshida, who also adapted A Silent Voice to film form, co-scripted Lu with Yuasa.)

Basically, it’s my observation of a modern trend. What I wanted to say is: Isn’t it better to say what you feel, what you think? Obviously you don’t have to do that every day, it’s not always good to be unrestrained. But I think what’s happening is that people are finding it really difficult to understand other people. Also, I think people generally “act out”; they behave in a certain way in one situation and differently in another. That’s human nature, but I think that the modern world is a bit awkward for everyone to live in. I think it would be nice if everyone could relax and loosen up a little bit more.

Another of the jokes in Lu Over the Wall is that the older characters think supernatural beings like Lu are terrifying, dangerous monsters, while the younger generation see them on the internet and think they’re cute and funny. Do you think the way people see the supernatural has changed, particularly in Japan?

I think people are getting more scared by these supernatural things, getting more conservative. Also, the Lu character is cute, but she’s not just cute. But what I wanted to express here is the acceptance of differences – some people are different, but that’s what they are and how they are.

Lu’s character designer Yoko Nemu is not well known in Britain yet. Can you talk about why you chose her?

Nemu uses really simple lines, and her style is quite serious and realistic. At the same time her style is very cute and sweet, so I really thought she would be perfect for this project. I had previously only read her realistic manga, but for characters like Lu and Lu’s father [who’s a giant walking shark!], she did really nice “manga”-like characters. She’s got so many ideas in her pocket, so it was great to work with her.

Your next project is Devilman crybaby, to be released on Netflix next year. Were you already a fan of the original Devilman manga by Go Nagai?

Devilman crybaby is a modern version of Devilman; you can’t really remake Devilman as it was. But I’m a great fan of the original Devilman [first published in 1972] and of Go Nagai. When I was working on Devilman crybaby, I was thinking: if Nagai was making it now, rather than in the 1970s, what would it be like? I hope the result is quite good, and I’m pretty sure that many people will like it. Obviously the look is quite different, but the core, the theme, is the same, I think. It’s still solid, it’s still Devilman.

How did you come to be offered the Devilman project?

I was actually talking to producers at Aniplex [the anime production company]. We were talking about various projects and plans and then they suggested Devilman. I love Devilman, but I was kind of scared. I would have wanted to work on it, but I wouldn’t have volunteered myself. I would have loved to do it if somebody asked me, so I was glad I was asked.

Have you had much contact with Go Nagai himself?

Actually, hardly ever. Nagai has always worked in a production system; I think he’s happy to leave things to other people to bring the best out of his work, his concepts. Hopefully he left Devilman Crybaby to us because he trusted us. But I was pleased to hear that Nagai saw The Night is Short and Lu, and he also bought Morimi’s novels.

Your recent works have been usually optimistic, whereas the original Devilman manga ends in a very despairing way.

[Warning: The next answer has possible spoilers for Devilman crybaby.] Yes, I am actually a little bit concerned for people who see Lu and then go on to Devilman crybaby – that would be quite a shock! But there is some celebration of redemption in crybaby. The story is quite dark, and there is a lot of despair, but all those scenes are there to reach salvation.

Can you say if the word “crybaby” in the title is a description of the story’s main character, Akira?

Yes, and it’s one of the main themes of the series.

For many of your fans, your 2004 Mind Game is your most wild, rough, spontaneous work. Do you think you will make something as wild as Mind Game again, or something even wilder, or have you pushed as far as you want to go in this direction?

I always want to try different things, so yes, if another opportunity arises, I would love to go for that too.

[More comments from this interview are given in an article on the AllTheAnime site.]