(Judge Dredd Megazine, Rebellion)

The Running Man, Stephen King’s 1982 novella about a gameshow which kills its contestants, ended with its hero grinning through a mask of blood and giving the TV producer the finger, before spoiler spoiler spoiler BANG. A quarter-century later, King favourably reviewed Suzanne Collins’ book The Hunger Games in Entertainment Weekly, and cackled, “Let’s see the makers of the movie version try to get a PG-13 on this baby.” The Lionsgate studio has just done that, in America at least (it’s rated 12A in Britain, with seven seconds of cuts).

The perceived mismatch between Hunger Games’ lurid subject – kids slaughtering each other on another homicidal gameshow – and its low certificate was the talking-point of March. Doubtless the film will be featured in the next wave of “violence on screen” history books, beside the similarly-rated The Dark Knight (aka The Vanishing Pencil). The Hunger Games’ smash at the boxoffice will beget many more films with low certificates and high shocks. Surely a remake of the archetype, Jaws, is due?

The subject-rating mismatch has fuelled a tedious fanboy meme; that Hunger Games is a watered-down rehash of the Japanese kids-killing-kids film Battle Royale (released in Britain in 2001, four days after 9/11). It’s partly cultish snobbery. Hunger Games is American and mainstream, whereas the subtitled Battle Royale only had an American release in the last few months. (The Japanese teens’ lethal weapons included common-or-garden firearms, which didn’t mesh with post-Columbine America.) But it’s mostly machismo.

Battle Royale was a “hard” 18, with a torrent of severed exploding heads and blood-bags bursting over Japanese school uniforms. The PG-13 Hunger Games uses fast-cut elisions for violence, relying on the comic-strip principle of the space between frames (like Psycho, where Saul Bass’s storyboarding fooled viewers into “seeing” a knife enter a nude female body). Worse, Hunger Games is viewable by the fanboys’ snotty little brothers, and their Twilight-reading sisters, and that’s unacceptable.

The premise in The Hunger Games and Battle Royale is “identical.” At least it is if you contrive your terms and forget that Battle Royale’s contest wasn’t a TV show; that its characters were a peer group from one classroom, not a scattering of couples and strangers from across America; and that it was a nightmare of the near-future, not a post-cataclysm, mirror-world dystopia. A greater divergence between Hunger Games and Battle Royale is that the Japanese film was an ensemble, remembered for its supporting turns from Takeshi Kitano and Chiaki Kuriyama (who’s the scowling minx reincarnated as “Gogo” in the first Kill Bill film, and who’s echoed in the “Johanna” character later in the Hunger Games books).

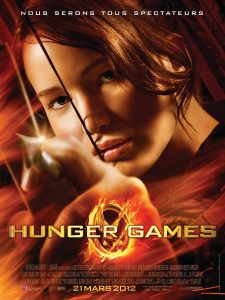

Hunger Games is a heroine’s tale, where that heroine – Katniss Everdeen, played by Jennifer Lawrence – is wholly earnest, even while the girl-and-two-boys love triangle is knowing and cleverly alienated. The appeal of Battle Royale was always, “What would you do?” Hunger Games asks, “What would you, the reader/audience, want her to do?” and feeds the answer back to the character. Admittedly this element is stronger in the book, and one of the main ways that the film disappoints; but the film adds its own perspective by turning the story into a screwed parody of The Wizard of Oz.

Instead of Kansas, Katniss lives in rusty, near-monochrome, neo-Depression District Twelve, briefly escaping into the green wood to hunt Bambi-deer and show her unsentimental stripes. Granted, she doesn’t bag the deer (the R-rated John Milius version would have had five minutes of skinning and gutting). More seriously, the film mutes District Twelve’s hardships. The book stresses that Katniss has grown up with starvation and death, unlike any of the squealing schoolkids of Battle Royale.

On strides Elizabeth Banks as a pink harlequin, with the matronly menace of Imelda Staunton in the Harry Potter films. There’s also a Bela Lugosi vibe to her “Welcome! Welcome!” as she selects tributes to kill each other in the Hunger Games. She draws the lottery ticket of Katniss’ little sister, who’s instantly separated by the camera from her out-of-focus peers, in a demonstration of how the games work. A shocked beat later, Katniss steps in to volunteer in her place, more like a mother than a sister, though she’s sworn never to have children. The girls’ true mother is incompetent, for reasons explained in the book but rushed on screen, so viewers may not register them. (A freer adaptation could have expediently killed her in the backstory.)

Katniss and fellow tribute Peeta (Josh Hutcherson) are whisked to the Capital by a high-tech train, but what awaits them is no future, but a phantasmagoria almost as retro as John Carter. In fact, the “Capital,” the overlord city which orchestrates the Hunger Games for its citizens’ pleasure and its vassals’ dread, could have been more phantasmagoric, more Oz-like. For all its shiny colours, the metropolis feels slightly subdued and second-hand for 21st-century cinema. It could have had crowd song routines, Azkaban décor or some CGI Phantom Menace phoniness. The whole set-up could have been turned cinematic, with Capital citizens watching the games in gaudy multiplexes.

Many reviewers have complained that the film should have rather been an archly specific satire on the mechanics of reality TV, as if we haven’t had enough of those already. Such a line would have yanked the story’s viewpoint out and away from Katniss, always peering outwards from the goldfish bowl. When she does a pre-fight interview with a blue-wigged John Tucci (who might have taken over a less disciplined film, like Richard Dawson’s host in the Schwarzenegger The Running Man), we see the Capital audience through Katniss’s eyes, incomprehensible faces and tides of noise.

Wisely, the film eschews Simon Cowell clone-figures, favouring broad, universal suggestions, like a shot of two privileged Capital children play-fighting before the event. There’s also a prologue in which TV commentators sentimentalise about how the Hunger Games “knit” the nation together. There was similar rhetoric in the alternate-history mockumentary, C.S.A.: The Confederate States of America (2004), which turned America into a twenty-first century slave nation. These deviant dystopia suggestions could have been taken further and deeper, but probably only in a TV-length series.

The film’s second half, the battle, is more exciting and flawed. It rattles through the incidents in the book to please the reading fans, telescoping the practicalities of survival (Katniss almost dies of thirst in the book) to get to the next bust-up. Unfortunately, the story’s key sequence – when Katniss pairs up with her countryman Peeta – occurs very late in the film, when the audience is likely to be drifting, and it feels pop-video synthetic. The point is meant to be that the youngsters are playing to the cameras to survive. If they build a story the audience likes, they get dropped favours from the outside that help them to live. Katniss, a teen hive of unexplored feelings and insecurities, must gloss those emotions into a three-act love narrative to tie off by the credits.

On film, it would take fine subtlety to convey this ambiguity, and a greater proportion of the story than in the source book. What we get are a few good illustrations, thoroughly undermined by a lurch into Twilight territory. It’s not a complete failure, thanks to the arresting contrast in the actors’ faces. Hutcherson as Peeta has square, infantile features; Lawrence’s grave face is voluptuously fruit-shaped, callowness and gravitas mingled. A film with leisure could have explored the miscommunications, between the pair, and between Katniss and herself. Instead, we get glib cuts to show the other boy in Katniss’s life (Gale, played by Liam Hemsworth), who’s stuck back home in District Twelve, glowering impotently at the televised action. Of course, this reduces the drama to exactly the kind of glossed story it’s meant to be critiquing: Team Peeta versus Team Gale.

The other great let-down is the deflating final battle, bland, low-rent and silly (there are CGI creatures); it’s changed a bit from the book, but not enough. Yet if The Hunger Games is stunted by its print source, then its box-office success poses a fascinating dilemma to franchise builders. It seems inevitable that The Hunger Games’ two sequels will be filmed (Catching Fire and Mockingjay), but they do not have a “Hollywood-friendly” ending. Indeed, Collins brutally denies such satisfactions, with a level of violence that makes Battle Royale pale. The film-makers have excuses for adapting the later books more loosely; they’re awkwardly constructed, some of the most “cinematic” material happens off-page, and the blindsiding shocks are cynically contrived. Still, it’s the story that the fanbase knows already, and if it doesn’t get what it wants…

(c) 2018 Rebellion A/S. Reprinted with permission.

[amazon_link asins=’B07BH4SBLC,B01844CXOY’ template=’ProductGrid’ store=’anime04c-21′ marketplace=’UK’ link_id=’f7706ab3-dd1f-4bc6-8579-bcd7ba879f85′]