(Neo, Uncooked Media – I also wrote a review of the first live-action Parasyte film for the MangaUK website.)

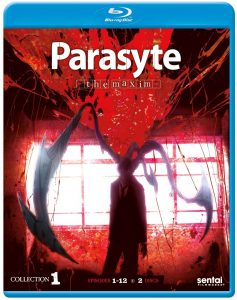

(Volume 1)

Parasyte starts with its money shot. A middle-aged husband and wife face each other in a dimmed room; then the man’s head splits and unfolds into a Venus flay-trap, with rows of teeth and a half-dozen eyes on stalks. The woman can’t scream, only gasp in halting, terrified breaths before the thing chomps her head off. Then a synthetic but spiky opening theme kicks in (by the group Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, heard on the end of Hunter x Hunter). The music races like a hysterical heartbeat, as if the woman’s terror outlives its owner.

In this SF-horror epic, people turn into flesh-eating nightmares after being infected by wormlike parasites. It feels like a film we’ve seen before, rooted in The Thing and Invasion of the Body Snatchers. But Parasyte’s twist is to tell its story, not through the eyes of the police or clueless bystanders, but through a freak accident. A schoolboy is attacked by a parasite in his bed and stops the creature worming to his brain, but gets the thing lodged in his hand instead.

In some ways, this is less like a horror movie than the story behind a horror movie. Against the background of a global invasion, it focuses on one invader which cocks up and gets stuck in its terrified victim. The invader is Migi (‘righty’), so named because he possesses the boy’s right arm. He can stretch and morph it into all kinds of bizaro shapes before eerily subsiding into a normal-looking hand again. (For other sentient anime hands, see Midori Days and Vampire Hunter D.)

His schoolboy host is Shinichi, a nervous, mildly geekish wallflower who must become a hero fighting for humanity on both concrete and abstract levels. Migi isn’t strictly his foe; most parasites are driven by a hunger to possess and eat humans, but Migi has his – or possibly her – hunger sated by Shinichi’s blood circulation, and is instead consumed by a curiosity that’s intense and dispassionate. Migi swiftly learns Japanese (from books, though there’s a joke later when we meet a parasite who learned his elocution from TV). As Migi explains eloquently to Shinichi, he’s on nobody’s ‘side.’ He’ll help Shinichi fight other parasite monsters for the pair’s shared protection, but he’ll cut out the lad’s eyes rather than let him expose Migi to the world.

The anime Parasyte was made in tandem with a live-action film version of the story; both are being released by Animatsu in two parts each. If you’ve seen the first live-action film, the anime covers roughly the same material, but with far more characters, plotlines and amplified themes. It’s a coming-of-age story, like a Shonen Jump saga with more gore but added nuance. For example, Shinichi’s heroic journey is triggered by Migi’s invasion of his hand, but it’s made clear that Shinichi is kind and courageous already. Migi can calm the boy in a crisis, but only by making him so logical and passionless that his friends cower away from him, as if he’s a pod person from Body Snatchers.

The story is enormously engrossing, largely because there’s no reset button, no way to take back the enormous developments that come quickly. The anime execution, by the Madhouse studio (Death Note, Ninja Scroll) is strong if not the studio’s best. Character expressions and acting are often good, sometimes stilted or cardboard. The morphing Migi is a gift to animators, and indeed has fine transformations, squashing and stretching ickily, but not as many as we might have hoped. The fight scenes are positively disappointing at times, as the parasites repetitively flail their tentacles and talk through their moves. Yet these fights can still be exciting, thanks to the characters and script – for example, when Shinichi must swallow his fear and walk into the blur of tentacles. The later fights improve.

Apart from the flexing Migi, the show has no ‘super-deformed’ humour, but the early episodes have a surprise touch of goofiness, like an old Hollywood teen comedy. This is quite enjoyable before the horror ramps up and Parasyte’s episodes start ending on masterful killer cliffhangers. Yet there are also moments of delicate humour. In one scene, Shinichi’s maybe-girlfriend tentatively takes his right hand, then hesitates and takes his left hand instead. The very next scene switches to two emotionless monsters about to have sex.

Parasyte’s gender politics are fascinating and controversial. They have plenty to attack; the manned-up Shinichi becomes a magnet for girls who continually fail the Bechdel test, including a supporting character – a bad girl turned stalker – who’s written cruelly and shallowly (which doesn’t stop her having good scenes). Parasyte also has a running obsession with motherhood which becomes comically obvious. Yet at the same time, there’s no worshipping of male ‘macho’ ideals, which the show provocatively presents as a female illusion. And then there’s the multishaped, freeform Migi at the show’s centre, portrayed as male in the manga and the live-action Parasytes… yet voiced in the anime by a woman.

[amazon_link asins=’B01C2W7UC4,B01GQJF6WK’ template=’ProductGrid’ store=’anime04c-21′ marketplace=’UK’ link_id=’c24fe1a1-54b7-43eb-920d-bdd45cd86e5f’]

prescription drugs without prior prescription https://graph.org/Understand-COVID-19-And-Know-The-Tricks-To-Avoid-It-From-Spreading—Medical-Services-02-21

You actually stated this superbly!

tadalafil generic https://kernyusa.estranky.sk/clanky/risk-factors-linked-to-anxiety-disorders-differ-between-women-and-men-during-the-pandemic.html

Amazing facts. Many thanks!

canadian online pharmacies https://andere.strikingly.com/

This is nicely said. !

online canadian pharmacy https://graph.org/Omicron-Variant-Symptoms-Is-An-Excessive-Amount-Of-Mucus-A-COVID-19-Symptom-02-24

Cheers, I appreciate this!

trust pharmacy canada https://telegra.ph/How-Has-The-COVID-19-Pandemic-Changed-Our-Lives-Globally-02-24

Awesome stuff. With thanks!

cialis tablets https://gerweds.over-blog.com/2022/03/modeling-covid-19-mortality-risk-in-toronto-canada-sciencedirect.html

You’ve made your point.

tadalafil 5mg https://keuybc.estranky.sk/clanky/30-facts-you-must-know–a-covid-cribsheet.html

Great information. Appreciate it.

online prescriptions without a doctor https://gwertvb.mystrikingly.com/

You made the point!

tadalafil without a doctor’s prescription https://telegra.ph/Is-It-Safe-To-Lift-COVID-19-Travel-Bans-04-06

Superb info, Thank you!

no 1 canadian pharcharmy online https://graph.org/The-Way-To-Get-Health-Care-At-Home-During-COVID-19—Health–Fitness-04-07

Nicely put, Regards.

cialis online https://chubo3.wixsite.com/canadian-pharmacy/post/what-parents-must-find-out-about-kids-and-covid-19

Cheers! I enjoy this!

canada online pharmacies https://canadian-pharmacies0.yolasite.com/

You actually mentioned that exceptionally well.

tadalafil 20mg https://pharmacy-online.yolasite.com/

Incredible quite a lot of valuable information.

tadalafil 20 mg https://kevasw.webgarden.com/

You actually stated this exceptionally well.

tadalafil without a doctor’s prescription https://62553dced4718.site123.me/

You said that adequately!

canadian pharmacy no prescription https://seketu.gonevis.com/high-10-tips-with-order-medicine-online-1/

Superb data, Kudos!

online prescriptions without a doctor https://site128620615.fo.team/

You actually suggested this wonderfully.

cialis 20mg prix en pharmacie https://625a9a98d5fa7.site123.me/blog/age-dependence-of-healthcare-interventions-for-covid-19-in-ontario-canada

With thanks, I value it.

canada drugs https://hernswe.gonevis.com/scientists-model-true-prevalence-of-covid-19-throughout-pandemic/

You said it perfectly.!

online drug store https://selomns.gonevis.com/a-modified-age-structured-sir-model-for-covid-19-type-viruses/

Many thanks! Wonderful information!

tadalafil 10 mg https://fwervs.gumroad.com/

Thank you! A good amount of facts.

tadalafil generic https://trosorin.mystrikingly.com/

Thanks! Good stuff!

cialis generic https://sasnd0.wixsite.com/cialis/post/impotent-victims-can-now-cheer-up-try-generic-tadalafil-men-health

Valuable knowledge. Regards!

canadian cialis https://626106aa4da69.site123.me/blog/new-step-by-step-roadmap-for-tadalafil-5mg

Point clearly utilized!.

online prescriptions without a doctor https://generic-cialis-20-mg.yolasite.com/

Wonderful forum posts. Thanks a lot!

buy cialis https://hsoybn.estranky.sk/clanky/tadalafil-from-india-vs-brand-cialis—sexual-health.html

You have made the point.

Generic cialis tadalafil https://skuvsbs.gonevis.com/when-tadalafil-5mg-competitors-is-good/

Fine tips. Thanks a lot.

cialis without a doctor’s prescription https://hemuyrt.livejournal.com/325.html

Amazing many of valuable info.

cialis online https://site373681070.fo.team/

You said it nicely.!

cialis 5mg https://sehytv.wordpress.com/

Cheers. An abundance of info.

cialis 5 mg https://ghswed.wordpress.com/2022/04/27/he-final-word-information-to-online-pharmacies/

Very good data, Kudos.

cialis without a doctor’s prescription https://kerbgsw.mystrikingly.com/

Tips effectively used.!

cialis https://kuebser.estranky.sk/clanky/supereasy-methods-to-study-every-part-about-online-medicine-order-discount.html

Many thanks, Awesome stuff.

tadalafil without a doctor’s prescription https://kerbiss.wordpress.com/2022/04/27/14/

Reliable data. With thanks!

cialis generico online https://kewburet.wordpress.com/2022/04/27/how-to-keep-your-workers-healthy-during-covid-19-health-regulations/

You actually stated this wonderfully.

cialis prices https://sernert.estranky.sk/clanky/confidential-information-on-online-pharmacies.html

Kudos! I enjoy it.

cialis online https://kertubs.mystrikingly.com/

Cheers, An abundance of posts.

cialis online https://626f977eb31c9.site123.me/blog/how-google-is-changing-how-we-approach-online-order-medicine-1

Truly plenty of excellent knowledge!

cialis 20mg prix en pharmacie https://canadian-pharmaceuticals-online.yolasite.com/

You actually suggested that superbly!

canadian pharmacies online https://online-pharmacies0.yolasite.com/

Thanks. Fantastic stuff.

northwestpharmacy https://6270e49a4db60.site123.me/blog/the-untold-secret-to-mastering-aspirin-in-just-7-days-1

You revealed that exceptionally well!

cialis lowest price https://deiun.flazio.com/

You have made the point!

cialis tablets https://kertyun.flazio.com/

Regards! Plenty of knowledge!

best canadian mail order pharmacies https://kerntyas.gonevis.com/the-mafia-guide-to-online-pharmacies/

You stated it terrifically!

cialis online https://kerbnt.flazio.com/

With thanks. Useful information.

cialis tablets australia http://nanos.jp/jmp?url=http://cialisonlinei.com/

Useful data. Many thanks.

cialis generic http://ime.nu/cialisonlinei.com

Thanks a lot, Numerous data!

cialis generico online https://womed7.wixsite.com/pharmacy-online/post/new-ideas-into-canada-pharmacies-never-before-revealed

Many thanks. Terrific stuff.

best canadian pharmacy https://kerntyast.flazio.com/

Kudos. Plenty of knowledge.

generic cialis https://sekyuna.gonevis.com/three-step-guidelines-for-online-pharmacies/

Nicely put, Kudos!

cialis generico https://gewrt.usluga.me/

You actually revealed this well!

cialis purchase online without prescription https://pharmacy-online.webflow.io/

Regards, I appreciate it.

cialis 20 mg best price https://canadian-pharmacy.webflow.io/

Thank you! Loads of stuff!

cialis generic https://site273035107.fo.team/

Many thanks! A lot of content!

cialis canadian pharmacy https://site656670376.fo.team/

Thanks! I like it.

online prescriptions without a doctor https://site561571227.fo.team/

With thanks! Very good information!

cialis tablets australia https://site102906154.fo.team/

Good forum posts. Many thanks!

canada drugs https://hekluy.ucraft.site/

Thanks, A lot of forum posts.

cialis 5mg prix https://kawsear.fwscheckout.com/

Incredible quite a lot of superb info.

cialis 20mg prix en pharmacie https://hertnsd.nethouse.ru/

You actually mentioned that superbly.

cialis canada https://uertbx.livejournal.com/402.html

Nicely put, Thank you.

tadalafil https://lwerts.livejournal.com/276.html

Thank you, Plenty of info.

cialis generico https://avuiom.sellfy.store/

Nicely put, Cheers!

trust pharmacy canada https://pharmacies.bigcartel.com/

Great data. Regards!

Generic cialis tadalafil https://kwersd.mystrikingly.com/

Nicely put. Regards!

canadian pharmacy meds https://gewsd.estranky.sk/clanky/drugstore-online.html

Very good tips. Thanks a lot!

generic for cialis https://kqwsh.wordpress.com/2022/05/16/what-everybody-else-does-when-it-comes-to-online-pharmacies/

With thanks, I appreciate it.

canadian pharmacy viagra http://site592154748.fo.team/

Really loads of very good data.

canadian rx https://lasert.gonevis.com/recommended-canadian-pharmacies-2/

You stated that exceptionally well!

cialis 20 mg http://aonubs.website2.me/

Kudos! A good amount of forum posts!

cialis 20mg prix en pharmacie https://dkyubn.bizwebs.com/

Regards! I enjoy this!

Cialis tadalafil https://asebg.bigcartel.com/canadian-pharmacy

Very good postings. Regards!

canada pharmacy online https://medicine-online.estranky.sk/clanky/understand-covid-19-and-know-the-tricks-to-avoid-it-from-spreading—–medical-services.html

Amazing many of fantastic information!

Canadian Pharmacies Shipping to USA https://kertvbs.webgarden.com/

Cheers. Excellent stuff.

online cialis https://disvaiza.mystrikingly.com/

This is nicely expressed! !

cialis 20mg https://swenqw.company.site/

You have made your stand quite nicely!.

cialis tablets https://kaswesa.nethouse.ru/

Lovely information. Thank you!

cialis 20mg prix en pharmacie https://628f789e5ce03.site123.me/blog/what-everybody-else-does-when-it-comes-to-canadian-pharmacies

Thanks a lot. I like this.

purchasing cialis on the internet https://canadian-pharmaceutical.webflow.io/

You actually mentioned that terrifically!

cialis 20mg prix en pharmacie http://pamelaliggins.website2.me/

Nicely put, Kudos!

psy-

psy-

cialis 5 mg http://pharmacy.prodact.site/

Incredible lots of useful info.

cialis tablets https://hub.docker.com/r/gserv/pharmacies

Excellent knowledge. Thank you!

canadian cialis https://hertb.mystrikingly.com/

Wow plenty of fantastic knowledge!

cialis from canada https://kedmnx.estranky.sk/clanky/online-medicine-tablets-shopping-the-best-manner.html

Awesome knowledge. Thanks a lot!

cialis 20mg https://selera.mystrikingly.com/

Thank you. Quite a lot of posts.

online canadian pharmacy https://ksorvb.estranky.sk/clanky/why-online-pharmacies-is-good-friend-to-small-business.html

You actually explained this effectively.

canadian pharmacy meds https://gevcaf.estranky.cz/clanky/safe-canadian-online-pharmacies.html

Really loads of good information!

canada pharmacy https://kwersv.proweb.cz/

Amazing loads of excellent knowledge!

tadalafil 20mg https://kwervb.estranky.cz/clanky/canadian-government-approved-pharmacies.html

Perfectly spoken certainly! !

tadalafil generic https://sdtyli.zombeek.cz

Thank you. Quite a lot of write ups.

buy cialis https://kwsde.zombeek.cz/

Wow tons of great info!

canadian pharmacy king https://heklrs.wordpress.com/2022/06/14/canadian-government-approved-pharmacies/

Fantastic postings. Many thanks!

canadian pharmacy no prescription https://iercvsw.wordpress.com/2022/06/14/canadian-pharmacies-the-fitting-manner/

Thanks, I appreciate it!

canadian pharmacies online prescriptions https://site955305180.fo.team/

Thanks a lot! Wonderful information.

canada pharmacy online http://site841934642.fo.team/

Nicely put, Kudos.

canadianpharmacy https://62b2f636ecec4.site123.me/blog/canadian-pharmaceuticals-online

Information very well used.!

canadian pharmacy online https://62b2ffff12831.site123.me/blog/canadian-pharmaceuticals-for-usa-sales

You actually revealed this exceptionally well!

tadalafil https://thefencefilm.co.uk/community/profile/hswlux/

Thank you, I enjoy it.

cialis 20mg https://anewearthmovement.org/community/profile/mefug/

Amazing advice. Many thanks.

cialis 20 mg best price http://sandbox.autoatlantic.com/community/profile/kawxvb/

Valuable knowledge. Many thanks.

canadian pharcharmy online http://lwerfa.iwopop.com/

Kudos! Ample knowledge.

no 1 canadian pharcharmy online http://herbsd.iwopop.com/

Really many of excellent data!

canadian pharmacy world http://kawerf.iwopop.com/

Nicely put. Thank you.

psikholog

psikholog

cialis from canada https://www.reddit.com/user/dotijezo/comments/9xlg6g/online_pharmacies/

Useful data. Appreciate it!

buy generic cialis https://my.desktopnexus.com/Pharmaceuticals/journal/canadian-pharmaceuticals-for-usa-sales-38346/

Cheers, Quite a lot of knowledge!

list of reputable canadian pharmacies https://www.formlets.com/forms/tH7aROl1ugDpCHqB/

Appreciate it. An abundance of postings!

northwest pharmacies https://www.divephotoguide.com/user/pharmaceuticals/

Helpful forum posts. Thanks a lot!

buy cialis without a doctor’s prescription https://www.formlets.com/forms/v7CoE3An9poMtRwF/

Many thanks, Valuable information.

buy generic cialis http://cialis.iwopop.com/

Many thanks, I appreciate it.

site

site

buy cialis without a doctor’s prescription https://pharmaceuticals.teachable.com/

Cheers. I like it.

stats

stats

Generic cialis tadalafil http://lsdevs.iwopop.com/

Truly loads of fantastic knowledge!

cialis 20mg prix en pharmacie https://hub.docker.com/repository/docker/canadianpharmacys/pharmacies_in_canada_shipping_to_usa

Kudos! I appreciate this!

UKRAINE

UKRAINE

Ukraine-war

Ukraine-war

movies

movies

gidonline

gidonline

generic cialis https://canadianpharmacy.teachable.com/

You actually explained that effectively.

tadalafil 5mg https://agrtyh.micro.blog/

Really many of beneficial data.

generic for cialis https://www.artstation.com/etnyqs6/profile

Seriously tons of superb knowledge.

mir dikogo zapada 4 sezon 4 seriya

mir dikogo zapada 4 sezon 4 seriya

cialis generic https://www.artstation.com/pharmacies

Regards, I value it!

web

web

film.8filmov.ru

film.8filmov.ru

Canadian Pharmacy USA https://www.formlets.com/forms/FgIl39avDRuHiBl4/

Beneficial content. Appreciate it!

cialis prices https://selaws.estranky.cz/clanky/canadian-government-approved-pharmacies.html

You revealed this really well!

video

video

cialis tablets australia https://kaswes.proweb.cz/

You have made your point quite nicely!.

canadian pharmaceuticals https://kvqtig.zombeek.cz/

Seriously all kinds of fantastic facts.

cialis 5 mg http://kwsedc.iwopop.com/

Whoa lots of useful knowledge.

cialis lowest price http://kwerks.iwopop.com/

Really plenty of useful material!

canadian government approved pharmacies https://drugscanada.teachable.com/

You’ve made your point pretty effectively.!

cialis online https://selaw.flazio.com/

Many thanks! I value it!

film

film

cialis https://gswera.livejournal.com/385.html

Superb info. Kudos.

canadian pharmacies without an rx https://canadianpharmaceutical.bigcartel.com/canadian-pharmaceuticals-online

Thanks, Numerous content!

canada pharmacy https://azuvh4.wixsite.com/pharmaceuticals-onli/post/london-drugs-canada

Amazing all kinds of beneficial advice!

cialis generico online https://hub.docker.com/r/pharmacies/online

Reliable stuff. Many thanks.

cialis tablets australia https://www.formlets.com/forms/N2BtJ3kPeJ3KclCw/

Kudos, Ample tips.

cialis canadian pharmacy https://www.divephotoguide.com/user/pharmacies

Well expressed really! !

medication without a doctors prescription https://hkwerf.micro.blog/

You said it adequately.!

cialis 20 mg best price https://my.desktopnexus.com/Canadian-pharmacies/journal/safe-canadian-online-pharmacies-38571/

Useful information. Cheers!

tadalafil 20mg https://canadian-government-approved-pharmacies.webflow.io/

Reliable data. Kudos.

generic for cialis https://lasevs.estranky.cz/clanky/pharmaceuticals-online-australia.html

Nicely put. Thanks!

tadalafil 10 mg https://kawerc.proweb.cz/

Many thanks. Useful information!

online pharmacy https://pedrew.zombeek.cz/

With thanks! I appreciate it.

canada online pharmacy https://fermser.flazio.com/

Superb data, Kudos!

discount canadian pharmacies https://londondrugscanada.bigcartel.com/london-drugs

Many thanks! Plenty of advice!

cialis generico https://canadapharmacy.teachable.com/

Seriously plenty of helpful info.

generic for cialis https://fofenp.wixsite.com/london-drugs-canada/en/post/pharmacies-shipping-to-usa-that/

Thanks. Plenty of stuff!

cialis purchase online without prescription https://swebas.livejournal.com/359.html

Cheers! Ample stuff.

medication without a doctors prescription https://lawert.micro.blog/

Cheers, I appreciate it.

cialis online https://canadian-pharmacies.webflow.io/

Valuable content. Kudos.

liusia-8-seriiaonlain

liusia-8-seriiaonlain

canadian pharmacy online https://my.desktopnexus.com/kawemn/journal/pharmaceuticals-online-australia-38678/

Reliable information. Many thanks.

tadalafil https://www.divephotoguide.com/user/drugs

Nicely put. Many thanks.

list of reputable canadian pharmacies https://hub.docker.com/r/dkwer/drugs

Cheers. A lot of content.

smotret-polnyj-film-smotret-v-khoroshem-kachestve

smotret-polnyj-film-smotret-v-khoroshem-kachestve

canadian cialis https://form.jotform.com/decote/canadian-pharmacies-shipping-to-the

Truly a good deal of awesome data.

cialis canada https://linktr.ee/canadianpharmacy

Wow loads of valuable knowledge!

cleantalkorg2.ru

cleantalkorg2.ru

canadian prescriptions online https://kawers.micro.blog/

Position nicely used..

filmgoda.ru

filmgoda.ru

rodnoe-kino-ru

rodnoe-kino-ru

medication without a doctors prescription https://mewser.mystrikingly.com/

You said it nicely.!

cialis https://sbwerd.estranky.sk/clanky/cialis-generic-pharmacy-online.html

Very good write ups. Thanks a lot!

tadalafil generic https://alewrt.flazio.com/

Very good forum posts. Many thanks.

tadalafil 20mg https://buycialisonline.fo.team/

You made your position quite nicely!!

stat.netstate.ru

stat.netstate.ru

buy cialis https://laswert.wordpress.com/

Amazing data. With thanks!

cialis 20mg prix en pharmacie https://kasheras.livejournal.com/283.html

Nicely put. With thanks.

tadalafil without a doctor’s prescription https://kwxcva.estranky.cz/clanky/cialis-20-mg.html

You expressed it exceptionally well!

cialis 20mg prix en pharmacie https://tadalafil20mg.proweb.cz/

Cheers! I enjoy it.

canadian cialis https://owzpkg.zombeek.cz/

Seriously many of very good tips.

tadalafil tablets http://lasweb.iwopop.com/

Really plenty of great data.

cialis https://buycialisonline.bigcartel.com/cialis-without-a-doctor-prescription

Truly quite a lot of good info.

buy generic cialis https://buycialisonline.teachable.com/

Perfectly spoken really! .

medication without a doctors prescription https://kalwer.micro.blog/

You said it terrifically.

purchasing cialis on the internet https://my.desktopnexus.com/Buycialis/journal/cialis-without-a-doctor-prescription-38780/

Really all kinds of excellent material!

sY5am

sY5am

cialis generico online https://www.divephotoguide.com/user/buycialisonline

You actually reported this fantastically!

cialis from canada https://hub.docker.com/r/tadalafil/20mg

Very good info. Appreciate it.

online prescriptions without a doctor https://tadalafil20mg.webflow.io/

You actually stated it exceptionally well!

tadalafil generic https://kswbnh.nethouse.ru/

Nicely put, Many thanks.

cialis canada https://www.formlets.com/forms/fpN4Ll8AEnDHBAkr/

Helpful posts. Appreciate it!

Cialis tadalafil https://form.jotform.com/ogmyn/buycialisonline

Thanks a lot! Loads of write ups.

cialis 20mg https://linktr.ee/buycialisonline

Regards! I like this!

cialis generic https://telegra.ph/Cialis-20mg-08-13

Terrific facts. Thanks.

canadian cialis https://graph.org/Tadalafil-20mg-08-13

Superb posts, Many thanks.

canadian pharmacy world https://kwenzx.nethouse.ru/

Many thanks! An abundance of info.

cialis tablets https://dwerks.nethouse.ru/

Thanks. Plenty of forum posts!

cialis https://form.jotform.com/ycaatk/canadian-pharmaceuticals-online-lis

Wow quite a lot of good knowledge!

canadian cialis https://linktr.ee/onlinepharmacies

Kudos, Valuable information.

tadalafil 5mg https://telegra.ph/Reputable-canadian-pharmaceuticals-online-08-12

Amazing all kinds of beneficial info.

online canadian pharmacies https://graph.org/Pharmacies-in-canada-shipping-to-usa-08-12

Incredible a lot of amazing information!

viagra canada https://telegra.ph/Recommended-canadian-pharmacies-08-12

You expressed it wonderfully!

cialis 20mg https://graph.org/Safe-canadian-online-pharmacies-08-12

Wonderful content. Thank you.

buy cialis without a doctor’s prescription https://linktr.ee/canadianpharmacies

Cheers. Great stuff!

Viagra generic https://buyviagraonlinee.mystrikingly.com/

Nicely put. Appreciate it!

tadalafil 20mg https://buyviagraonline.estranky.sk/clanky/buy-viagra-without-prescription-pharmacy-online.html

With thanks, Lots of write ups.

cialis pills https://buyviagraonline.flazio.com/

Cheers, Excellent information!

cialis from canada https://buyviagraonline.fo.team/

Nicely put. Cheers!

Dom drakona

Dom drakona

JGXldbkj

JGXldbkj

aOuSjapt

aOuSjapt

cialis 20 mg https://noyano.wixsite.com/buyviagraonline

You’ve made your point extremely effectively.!

Viagra canada https://buyviagraonlinet.wordpress.com/

You said it adequately..

cialis lowest price https://buyviagraonl.livejournal.com/386.html

Nicely put, Cheers.

cialis 5 mg https://buyviagraonline.nethouse.ru/

Thank you! I enjoy this.

Viagra generika https://buyviagraonline.estranky.cz/clanky/can-i-buy-viagra-without-prescription.html

Beneficial material. Regards.

medication without a doctors prescription https://buyviagraonline.proweb.cz/

You said this superbly.

online cialis https://buyviagraonline.zombeek.cz/

Many thanks. I value this.

ìûøëåíèå

ìûøëåíèå

psikholog moskva

psikholog moskva

Viagra for daily use http://jso7c59f304.iwopop.com/

Awesome forum posts. Regards!

Usik Dzhoshua 2 2022

Usik Dzhoshua 2 2022

purchasing cialis on the internet https://buyviagraonline.bigcartel.com/viagra-without-a-doctor-prescription

Lovely info, Thanks a lot!

buy cialis without a doctor’s prescription https://buyviagraonline.teachable.com/

Amazing information. Many thanks!

Viagra 20 mg https://telegra.ph/How-to-get-viagra-without-a-doctor-08-18

Whoa all kinds of beneficial advice.

cialis 20mg https://graph.org/Buying-viagra-without-a-prescription-08-18

Nicely put. Appreciate it!

Dim Drakona 2022

Dim Drakona 2022

cialis 20mg prix en pharmacie https://buyviagraonline.micro.blog/

Seriously a lot of excellent knowledge.

Viagra generico https://my.desktopnexus.com/buyviagraonline/journal/online-viagra-without-a-prescriptuon-38932/

Cheers. Useful information.

Buy viagra online https://www.divephotoguide.com/user/buyviagraonline

Nicely put, Thanks.

Buy viagra https://hub.docker.com/r/buyviagraonline/viagra

Seriously tons of fantastic material!

Cheap cialis https://viagrawithoutprescription.webflow.io/

Very good info, Kudos.

TwnE4zl6

TwnE4zl6

Viagra 5 mg funziona https://form.jotform.com/222341315941044

With thanks, I appreciate this.

Tadalafil https://linktr.ee/buyviagraonline

You said it perfectly..

Viagra for daily use https://buyviagraonline.home.blog/

Thank you. I enjoy it!

canadian mail order pharmacies https://canadianpharmaceuticalsonline.home.blog/

Seriously plenty of good tips.

psy 3CtwvjS

psy 3CtwvjS

cialis https://onlineviagra.mystrikingly.com/

Regards. Quite a lot of posts!

cialis 20 mg best price https://reallygoodemails.com/onlineviagra

Nicely put. Regards.

cialis 20 mg best price https://viagraonline.estranky.sk/clanky/viagra-without-prescription.html

You stated that fantastically.

lalochesia

lalochesia

cialis canada https://viagraonlineee.wordpress.com/

You said it nicely.!

cialis 5 mg https://viagraonline.home.blog/

Thanks a lot. Fantastic stuff!

tadalafil tablets https://viagraonlinee.livejournal.com/492.html

Regards. Ample posts!

tadalafil without a doctor’s prescription https://onlineviagra.flazio.com/

Thanks, I value it!

Tadalafil tablets https://onlineviagra.fo.team/

Terrific data. Regards!

Generic cialis tadalafil https://www.kadenze.com/users/canadian-pharmaceuticals-for-usa-sales

You actually suggested that really well!

cialis https://linktr.ee/canadianpharmaceuticalsonline

Thank you! I value this.

online cialis https://disqus.com/home/forum/canadian-pharmaceuticals-online/

Reliable posts. Many thanks.

cialis 5mg https://500px.com/p/canadianpharmaceuticalsonline

You actually revealed it effectively.

film onlinee

film onlinee

cialis 5 mg https://dailygram.com/index.php/blog/1155353/we-know-quite-a-bit-about-covid-19/

Thanks. Loads of knowledge.

programma peredach na segodnya

programma peredach na segodnya

cialis 5mg https://challonge.com/en/canadianpharmaceuticalsonlinemt

Amazing quite a lot of excellent knowledge.

cialis 5 mg https://500px.com/p/listofcanadianpharmaceuticalsonline

With thanks, A lot of knowledge.

cialis from canada https://www.seje.gov.mz/question/canadian-pharmacies-shipping-to-usa/

Truly tons of terrific tips.

tadalafil 5mg https://challonge.com/en/canadianpharmaciesshippingtousa

Really plenty of beneficial advice.

cialis 20mg prix en pharmacie https://challonge.com/en/canadianpharmaceuticalsonlinetousa

Thank you. An abundance of knowledge.

canadian pharmacies online prescriptions https://pinshape.com/users/2441403-canadian-pharmaceuticals-online

You explained that perfectly.

online drug store https://www.scoop.it/topic/canadian-pharmaceuticals-online

Beneficial knowledge. Regards!

cialis 20 mg https://reallygoodemails.com/canadianpharmaceuticalsonline

Reliable write ups. Appreciate it!

cialis 20mg prix en pharmacie pinshape.com/users/2441621-canadian-pharmaceutical-companies

Terrific facts. With thanks!

cialis online https://pinshape.com/users/2441621-canadian-pharmaceutical-companies

You actually said it well.

Cialis tadalafil https://reallygoodemails.com/canadianpharmaceuticalcompanies

Awesome material. Kudos!

stromectol reviews https://pinshape.com/users/2445987-order-stromectol-over-the-counter

Kudos, Great stuff!

Viagra bula https://reallygoodemails.com/orderstromectoloverthecounter

Amazing forum posts. Thanks.

Viagra rezeptfrei https://challonge.com/en/orderstromectoloverthecounter

Regards! Great stuff.

Viagra bula https://500px.com/p/orderstromectoloverthecounter

Thank you, I value it!

psycholog-v-moskve.ru

psycholog-v-moskve.ru

psycholog-moskva.ru

psycholog-moskva.ru

Low cost viagra 20mg https://www.seje.gov.mz/question/order-stromectol-over-the-counter-6/

Incredible tons of superb information.

Viagra cost https://canadajobscenter.com/author/buystromectol/

Info well applied.!

Viagra kaufen https://canadajobscenter.com/author/canadianpharmaceuticalsonline/

You expressed it effectively!

drugs for sale https://aoc.stamford.edu/profile/canadianpharmaceuticalsonline/

You actually expressed it fantastically.

Viagra generico online https://canadianpharmaceuticalsonline.bandcamp.com/releases

This is nicely put. .

canada drugs https://ktqt.ftu.edu.vn/en/question list/canadian-pharmaceuticals-for-usa-sales/

Many thanks. I enjoy this.

Tadalafil 20 mg https://www.provenexpert.com/canadian-pharmaceuticals-online/

Great stuff. Many thanks.

3qAIwwN

3qAIwwN

is stromectol safe https://aoc.stamford.edu/profile/Stromectol/

You’ve made your stand extremely well..

Buy generic viagra https://ktqt.ftu.edu.vn/en/question list/order-stromectol-over-the-counter-10/

Cheers. Numerous postings!

Buy viagra https://orderstromectoloverthecounter.bandcamp.com/releases

Wonderful content. With thanks.

Interactions for viagra https://www.provenexpert.com/order-stromectol-over-the-counter12/

You revealed this very well!

Viagra reviews https://www.repairanswers.net/question/order-stromectol-over-the-counter-2/

You actually explained this perfectly!

video-2

video-2

Tadalafil https://www.repairanswers.net/question/stromectol-order-online/

Nicely put, With thanks!

Viagra vs viagra https://canadajobscenter.com/author/arpreparof1989/

Thanks a lot, I enjoy it!

sezons.store

sezons.store

what is stromectol used for https://aoc.stamford.edu/profile/goatunmantmen/

Incredible many of useful information!

where to buy stromectol uk https://web904.com/stromectol-buy/

Kudos, Plenty of write ups.

socionika-eniostyle.ru

socionika-eniostyle.ru

stromectol espana https://web904.com/buy-ivermectin-online-fitndance/

Cheers! Terrific information.

Viagra sans ordonnance https://glycvimepedd.bandcamp.com/releases

This is nicely expressed! .

psy-news.ru

psy-news.ru

Viagra from canada https://canadajobscenter.com/author/ereswasint/

Kudos, I appreciate this!

How does viagra work https://aoc.stamford.edu/profile/hispennbackwin/

You actually expressed it adequately.

buy viagra usa https://bursuppsligme.bandcamp.com/releases

Valuable forum posts. Regards!

Viagra great britain https://pinshape.com/users/2461310-canadian-pharmacies-shipping-to-usa

You expressed that exceptionally well!

Viagra vs viagra https://pinshape.com/users/2462760-order-stromectol-over-the-counter

Whoa tons of great data.

Viagra cost https://pinshape.com/users/2462910-order-stromectol-online

You actually said that perfectly!

Viagra bula 500px.com/p/phraspilliti

Cheers, Helpful information!

000-1

000-1

3SoTS32

3SoTS32

3DGofO7

3DGofO7

Viagra tablets australia https://web904.com/canadian-pharmaceuticals-for-usa-sales/

Many thanks! Wonderful information.

Viagra vs viagra vs levitra https://500px.com/p/skulogovid/?view=groups

Kudos! I like this.

canada online pharmacies https://500px.com/p/bersavahi/?view=groups

Superb facts, With thanks!

canadian online pharmacies https://reallygoodemails.com/canadianpharmaceuticalsonlineusa

Wow a lot of terrific tips.

Viagra generico https://www.provenexpert.com/canadian-pharmaceuticals-online-usa/

You said it nicely.!

Viagra 20mg https://sanangelolive.com/members/pharmaceuticals

Fantastic material, With thanks!

northwest pharmacies https://melaninterest.com/user/canadian-pharmaceuticals-online/?view=likes

Thank you, Awesome information!

Viagra 20mg https://haikudeck.com/canadian-pharmaceuticals-online-personal-presentation-827506e003

Amazing quite a lot of beneficial tips!

Cheap viagra https://buyersguide.americanbar.org/profile/420642/0

Thanks! I like it!

Buy generic viagra https://experiment.com/users/canadianpharmacy

You explained that effectively!

canadian drug https://slides.com/canadianpharmaceuticalsonline

Regards, Ample facts!

Canadian viagra https://challonge.com/esapenti

You revealed this very well!

Viagra rezeptfrei https://challonge.com/gotsembpertvil

Thank you. I appreciate this!

Viagra coupon https://challonge.com/citlitigolf

You made the point.

Viagra kaufen https://order-stromectol-over-the-counter.estranky.cz/clanky/order-stromectol-over-the-counter.html

Whoa quite a lot of terrific info.

Interactions for viagra https://soncheebarxu.estranky.cz/clanky/stromectol-for-head-lice.html

Excellent write ups. Thank you!

Discount viagra https://lehyriwor.estranky.sk/clanky/stromectol-cream.html

Amazing write ups. Thanks a lot!

Viagra cost https://dsdgbvda.zombeek.cz/

Terrific knowledge. Many thanks!

Viagra generique https://inflavnena.zombeek.cz/

Helpful facts. Thanks a lot.

wwwi.odnoklassniki-film.ru

wwwi.odnoklassniki-film.ru

Tadalafil 20 mg https://www.myscrsdirectory.com/profile/421708/0

This is nicely said. !

Viagra levitra https://supplier.ihrsa.org/profile/421717/0

Thanks a lot! I appreciate this.

Viagra uk https://wefbuyersguide.wef.org/profile/421914/0

Fantastic material. Appreciate it!

Viagra great britain https://legalmarketplace.alanet.org/profile/421920/0

Seriously a good deal of terrific material!

pharmacy https://moaamein.nacda.com/profile/422018/0

Really lots of terrific data.

Cheap viagra https://www.audiologysolutionsnetwork.org/profile/422019/0

Kudos. Lots of knowledge.

Tadalafil 20 mg https://network.myscrs.org/profile/422020/0

Appreciate it. An abundance of data!

highest rated canadian pharmacies https://sanangelolive.com/members/canadianpharmaceuticalsonlineusa

You have made your position quite well.!

stromectol france https://sanangelolive.com/members/girsagerea

Superb posts. Thanks a lot!

Buy generic viagra https://www.ecosia.org/search?q=“My Canadian Pharmacy – Extensive Assortment of Medications – 2022”

Thanks a lot, Valuable information!

Viagra reviews https://www.mojomarketplace.com/user/Canadianpharmaceuticalsonline-EkugcJDMYH

Good write ups. Many thanks.

Low cost viagra 20mg https://seedandspark.com/user/canadian-pharmaceuticals-online

Thank you! Fantastic information!

Viagra vs viagra vs levitra https://www.giantbomb.com/profile/canadapharmacy/blog/canadian-pharmaceuticals-online/265652/

Thanks a lot. Helpful information!

Viagra sans ordonnance https://feeds.feedburner.com/bing/Canadian-pharmaceuticals-online

Great posts. Regards.

cialis canadian pharmacy https://search.gmx.com/web/result?q=“My Canadian Pharmacy – Extensive Assortment of Medications – 2022”

Regards, Plenty of advice.

rftrip.ru

rftrip.ru

Viagra manufacturer coupon https://search.seznam.cz/?q=“My Canadian Pharmacy – Extensive Assortment of Medications – 2022”

Amazing information. Many thanks.

Tadalafil https://sanangelolive.com/members/unsafiri

Thank you. Helpful information.

canada pharmacies online prescriptions

You actually mentioned it wonderfully.

Tadalafil 20 mg https://swisscows.com/en/web?query=“My Canadian Pharmacy – Extensive Assortment of Medications – 2022”

Really a lot of beneficial knowledge!

Viagra dosage https://www.dogpile.com/serp?q=“My Canadian Pharmacy – Extensive Assortment of Medications – 2022”

You said it nicely..

Viagra canada

You actually reported that exceptionally well.

Viagra coupon https://search.givewater.com/serp?q=“My Canadian Pharmacy – Extensive Assortment of Medications – 2022”

You actually explained it fantastically!

Viagra coupon https://www.bakespace.com/members/profile/Сanadian pharmaceuticals for usa sales/1541108/

You explained that effectively.

How does viagra work

Useful stuff. Thanks!

How does viagra work https://results.excite.com/serp?q=“My Canadian Pharmacy – Extensive Assortment of Medications – 2022”

Cheers! Good stuff!

cialis canadian pharmacy https://www.infospace.com/serp?q=“My Canadian Pharmacy – Extensive Assortment of Medications – 2022”

Wow loads of amazing info!

dolpsy.ru

dolpsy.ru

Interactions for viagra https://headwayapp.co/canadianppharmacy-changelog

Really many of amazing knowledge!

canadian pharmacys https://results.excite.com/serp?q=“My Canadian Pharmacy – Extensive Assortment of Medications – 2022”

You made your stand very clearly!.

canada pharmacies online prescriptions https://canadianpharmaceuticalsonline.as.me/schedule.php

Regards. I enjoy this!

5 mg viagra coupon printable https://feeds.feedburner.com/bing/stromectolnoprescription

You expressed it perfectly.

Viagra generic https://reallygoodemails.com/orderstromectoloverthecounterusa

You expressed it perfectly!

kin0shki.ru

kin0shki.ru

3o9cpydyue4s8.ru

3o9cpydyue4s8.ru

treating scabies with stromectol https://aoc.stamford.edu/profile/cliclecnotes/

Factor effectively utilized!.

dose of stromectol https://pinshape.com/users/2491694-buy-stromectol-fitndance

Thanks. Fantastic information.

purchase stromectol online https://www.provenexpert.com/medicament-stromectol/

Really all kinds of good advice!

mb588.ru

mb588.ru

stromectol mites https://challonge.com/bunmiconglours

You said it very well..

Viagra 5mg prix https://theosipostmouths.estranky.cz/clanky/stromectol-biam.html

Truly quite a lot of valuable tips.

history-of-ukraine.ru news ukraine

history-of-ukraine.ru news ukraine

Viagra 5 mg https://tropkefacon.estranky.sk/clanky/buy-ivermectin-fitndance.html

Kudos! I appreciate this.

newsukraine.ru

newsukraine.ru

Viagra uk https://www.midi.org/forum/profile/89266-canadianpharmaceuticalsonline

Wow a good deal of excellent info.

Viagra reviews https://dramamhinca.zombeek.cz/

You actually expressed this very well!

Viagra canada https://sanangelolive.com/members/thisphophehand

This is nicely said. .

canadian pharmacy world https://motocom.co/demos/netw5/askme/question/canadian-pharmaceuticals-online-5/

Cheers. Plenty of material!

edu-design.ru

edu-design.ru

tftl.ru

tftl.ru

Viagra 20 mg best price https://www.infospace.com/serp?q=“My Canadian Pharmacy – Extensive Assortment of Medications – 2022”

Whoa tons of amazing material!

canada drug https://zencastr.com/@pharmaceuticals

Wow plenty of useful data.

stromectol posologie https://aleserme.estranky.sk/clanky/stromectol-espana.html

Wow lots of useful tips!

stromectol rosacea https://orderstromectoloverthecounter.mystrikingly.com/

Helpful postings. Thanks!

stromectol dosage table https://stromectoloverthecounter.wordpress.com/

Nicely put. Appreciate it.

Viagra lowest price https://buystromectol.livejournal.com/421.html

Helpful advice. Thanks a lot!

Viagra lowest price https://orderstromectoloverthecounter.flazio.com/

Many thanks, I like it.

Viagra dosage https://search.lycos.com/web/?q=“My Canadian Pharmacy – Extensive Assortment of Medications – 2022”

Thanks a lot. Valuable information!

highest rated canadian pharmacies https://conifer.rhizome.org/pharmaceuticals

Nicely put. Regards!

stromectol india https://telegra.ph/Order-Stromectol-over-the-counter-10-29

Nicely put, Thanks a lot.

Canadian viagra https://graph.org/Order-Stromectol-over-the-counter-10-29-2

Wow loads of superb advice!

brutv

brutv

facts stromectol https://orderstromectoloverthecounter.fo.team/

Perfectly spoken really. !

stromectol generic https://orderstromectoloverthecounter.proweb.cz/

You actually revealed it well!

Viagra rezeptfrei https://orderstromectoloverthecounter.nethouse.ru/

Regards, A good amount of posts!

Viagra for sale https://sandbox.zenodo.org/communities/canadianpharmaceuticalsonline/

Well expressed really! .

Viagra for sale https://demo.socialengine.com/blogs/2403/1227/canadian-pharmaceuticals-online

Very good material. Thank you.

site 2023

site 2023

canadian viagra https://pharmaceuticals.cgsociety.org/jvcc/canadian-pharmaceuti

Good postings. Thanks a lot.

global pharmacy canada https://taylorhicks.ning.com/photo/albums/best-canadian-pharmaceuticals-online

Nicely put. Many thanks!

Viagra vs viagra https://my.afcpe.org/forums/discussion/discussions/reputable-canadian-pharmaceuticals-online

With thanks, Lots of knowledge!

Viagra tablets australia https://www.dibiz.com/ndeapq

You actually explained that effectively.

Cheap viagra https://www.podcasts.com/canadian-pharmacies-shipping-to-usa

Thanks, A good amount of advice.

Viagra vs viagra https://canadianpharmaceuticals.educatorpages.com/pages/canadian-pharmacies-shipping-to-usa

You actually said it effectively!

online pharmacies https://soundcloud.com/canadian-pharmacy

Helpful information. Many thanks.

Tadalafil tablets https://peatix.com/user/14373921/view

Wow lots of useful knowledge.

canadian drugstore https://www.cakeresume.com/me/best-canadian-pharmaceuticals-online

You actually reported that perfectly.

Generic viagra https://dragonballwiki.net/forum/canadian-pharmaceuticals-online-safe/

Terrific tips. Thanks a lot.

Viagra tablets https://the-dots.com/projects/covid-19-in-seven-little-words-848643

Regards! Plenty of data!

Canadian viagra https://jemi.so/canadian-pharmacies-shipping-to-usa

Whoa a good deal of useful material!

Viagra kaufen https://www.homify.com/ideabooks/9099923/reputable-canadian-pharmaceuticals-online

Good posts, Thank you.

Viagra vs viagra https://medium.com/@pharmaceuticalsonline/canadian-pharmaceutical-drugstore-2503e21730a5

Very good stuff. Thanks a lot!

Viagra generika https://infogram.com/canadian-pharmacies-shipping-to-usa-1h1749v1jry1q6z

Cheers! Very good stuff!

canada viagra https://pinshape.com/users/2507399-best-canadian-pharmaceuticals-online

Nicely put, Thank you!

Viagra daily https://aoc.stamford.edu/profile/upogunem/

You actually suggested that exceptionally well!

buy viagra online usa https://500px.com/p/maybenseiprep/?view=groups

Many thanks! Fantastic stuff!

Viagra generico https://challonge.com/ebtortety

Wow quite a lot of useful data.

Interactions for viagra https://sacajegi.estranky.cz/clanky/online-medicine-shopping.html

Very good advice. Regards!

Viagra coupon https://speedopoflet.estranky.sk/clanky/international-pharmacy.html

Cheers! A lot of write ups!

canadian government approved pharmacies https://dustpontisrhos.zombeek.cz/

Really loads of helpful data.

Discount viagra https://sanangelolive.com/members/maiworkgendty

You’ve made the point!

Viagra uk https://issuu.com/lustgavalar

Nicely put, Many thanks.

Interactions for viagra https://calendly.com/canadianpharmaceuticalsonline/onlinepharmacy

Wow a good deal of excellent info.

canadian pharmacy online 24 https://aoc.stamford.edu/profile/uxertodo/

You suggested it fantastically.

canadian prescription drugstore https://www.wattpad.com/user/Canadianpharmacy

Amazing information. Regards.

Viagra vs viagra https://pinshape.com/users/2510246-medicine-online-shopping

You stated that really well.

sitestats01

sitestats01

1c789.ru

1c789.ru

cttdu.ru

cttdu.ru

Online viagra https://500px.com/p/reisupvertketk/?view=groups

Seriously loads of wonderful tips.

Viagra generico online https://www.provenexpert.com/online-order-medicine/

Thanks. Numerous material!

Viagra sans ordonnance https://challonge.com/ebocivid

You’ve made your position quite well..

Viagra generico https://obsusilli.zombeek.cz/

You actually reported that very well!

Viagra canada https://sanangelolive.com/members/contikegel

Great forum posts. Thanks a lot.

Viagra or viagra https://rentry.co/canadianpharmaceuticalsonline

Really a good deal of great facts.

Viagra from canada https://tawk.to/canadianpharmaceuticalsonline

Many thanks! I like it!

canadian pharmacycanadian pharmacy https://canadianpharmaceuticalsonline.tawk.help/article/canadian-pharmacies-shipping-to-usa

Incredible all kinds of fantastic data.

Viagra 20mg https://sway.office.com/bwqoJDkPTZku0kFA

You actually reported this terrifically!

How does viagra work https://canadianpharmaceuticalsonline.eventsmart.com/2022/11/20/canadian-pharmaceuticals-for-usa-sales/

Valuable content. Cheers.

northwestpharmacy https://suppdentcanchurch.estranky.cz/clanky/online-medicine-order-discount.html

Thank you! I like this!

canadian drugstore https://aoc.stamford.edu/profile/tosenbenlren/

Nicely put, Thanks!

Viagra for sale https://pinshape.com/users/2513487-online-medicine-shopping

Kudos. I enjoy it!

1703

1703

hdserial2023.ru

hdserial2023.ru

Viagra kaufen https://500px.com/p/meyvancohurt/?view=groups

Incredible a lot of great knowledge.

serialhd2023.ru

serialhd2023.ru

prescription drugs without prior prescription https://www.provenexpert.com/pharmacy-online/

Thanks a lot. Lots of content!

Canadian viagra https://challonge.com/townsiglutep

Thanks! Numerous data.

matchonline2022.ru

matchonline2022.ru

Viagra pills https://appieloku.estranky.cz/clanky/online-medicine-to-buy.html

You stated it superbly!

Viagra 5mg prix https://scisevitrid.estranky.sk/clanky/canada-pharmacies.html

Excellent information. Kudos.

Viagra canada https://brujagflysban.zombeek.cz/

Many thanks! Ample facts!

Viagra generico online https://aoc.stamford.edu/profile/plumerinput/

You actually reported this effectively.

Viagra pills https://pinshape.com/users/2517016-cheap-ed-drugs

Cheers. I value this.

Buy viagra https://www.provenexpert.com/best-erectile-pills/

Reliable stuff. With thanks!

bit.ly/3OEzOZR

bit.ly/3OEzOZR

bit.ly/3gGFqGq

bit.ly/3gGFqGq

bit.ly/3ARFdXA

bit.ly/3ARFdXA

bit.ly/3ig2UT5

bit.ly/3ig2UT5

Viagra from canada https://challonge.com/afersparun

Nicely put. Many thanks.

bit.ly/3GQNK0J

bit.ly/3GQNK0J

Viagra prices https://plancaticam.estranky.cz/clanky/best-drugs-for-ed.html

Kudos! I enjoy this!

How does viagra work https://piesapalbe.estranky.sk/clanky/buy-erectile-dysfunction-medications-online.html

Amazing facts. Thanks a lot.

ed drugs list https://wallsawadar.zombeek.cz/

Nicely put, With thanks!

legitimate canadian mail order pharmacies https://www.cakeresume.com/me/canadian-pharmaceuticals-online/

You actually revealed that well.

bep5w0Df

bep5w0Df

Canadian viagra https://canadianpharmaceuticalsonline.studio.site/

Regards! Fantastic information!

canada drugs https://en.gravatar.com/canadianpharmaceuticalcompanies

Truly a lot of great advice!

Viagra vs viagra vs levitra https://www.viki.com/users/pharmaceuticalsonline/about

Excellent forum posts. Thanks a lot.

www

www

canadian pharmacy online https://canadianpharmaceuticalsonline.blog.jp/archives/19372004.html

Many thanks. Excellent stuff.

Viagra 5mg prix https://canadianpharmaceuticalsonline.doorblog.jp/archives/19385382.html

You actually stated it perfectly.

pharmacy canada https://canadianpharmaceuticalsonline.ldblog.jp/archives/19386301.html

Many thanks, A lot of advice.

Viagra prices https://canadianpharmaceuticalsonline.dreamlog.jp/archives/19387310.html

You mentioned it terrifically.

Viagra great britain https://canadianpharmaceuticalsonline.publog.jp/archives/16846649.html

Seriously tons of valuable info.

Viagra generique https://canadianpharmaceuticalsonline.livedoor.biz/archives/17957096.html

Fine stuff. Kudos!

icf

icf

24hours-news

24hours-news

rusnewsweek

rusnewsweek

uluro-ado

uluro-ado

canadian pharmacy cialis https://canadianpharmaceuticalsonline.diary.to/archives/16857199.html

Nicely put. Thank you.

Viagra 20mg https://canadianpharmaceuticalsonline.weblog.to/archives/19410199.html

Thanks. I like this!

cialis from canada https://canadianpharmaceuticalsonline.bloggeek.jp/archives/16871680.html

Nicely put. Cheers.

Cheap viagra https://canadianpharmaceuticalsonline.blogism.jp/archives/17866152.html

Cheers. I value it!

Viagra coupon https://canadianpharmaceuticalsonline.blogo.jp/archives/19436771.html

Wow many of great knowledge.

canadian pharmacys https://canadianpharmaceuticalsonline.blogto.jp/archives/19498043.html

Many thanks! Useful stuff!

Viagra rezeptfrei https://canadianpharmaceuticalsonline.gger.jp/archives/18015248.html

Thank you! Wonderful information.

irannews.ru

irannews.ru

klondayk2022

klondayk2022

Viagra coupon https://canadianpharmaceuticalsonline.golog.jp/archives/16914921.html

Really quite a lot of valuable material!

canadian pharmacies that are legit https://canadianpharmaceuticalsonline.liblo.jp/archives/19549081.html

Incredible tons of beneficial data.

Viagra alternative https://canadianpharmaceuticalsonline.myjournal.jp/archives/18054504.html

Excellent tips. Cheers!

Canadian Pharmacy USA https://canadianpharmaceuticalsonline.mynikki.jp/archives/16957846.html

Whoa plenty of very good advice!

canadian pharmacy no prescription https://pinshape.com/users/2528098-canadian-pharmacy-online

Kudos, I enjoy it.

canada online pharmacy https://gravatar.com/kqwsh

Appreciate it. Numerous information.

Buy viagra https://www.buymeacoffee.com/pharmaceuticals

Kudos, I enjoy it.

online drug store https://telegra.ph/Canadian-pharmacy-drugs-online-12-11

You said that very well!

Viagra generique https://graph.org/Canadian-pharmacies-online-12-11

Many thanks, Quite a lot of tips.

Cheap viagra https://canadianonlinepharmacieslegitimate.flazio.com/

Thank you! I like it!

canadian pharmacy https://halttancentnin.livejournal.com/301.html

You revealed this very well!

Viagra vs viagra https://app.roll20.net/users/11413335/canadian-pharmaceuticals-online-shipping

You have made your point!

Viagra levitra https://linktr.ee/canadianpharmaceuticalsonlineu

Amazing info. Regards!

How does viagra work https://onlinepharmaciesofcanada.bigcartel.com/best-canadian-online-pharmacy

You suggested it exceptionally well!

tqmFEB3B

tqmFEB3B

Viagra 5 mg https://hub.docker.com/r/canadadiscountdrug/pharmaceuticals

Reliable data. Kudos!

Viagra rezeptfrei https://pharmacy-online.teachable.com/

Cheers, Great stuff!

Viagra from canada https://experiment.com/users/canadiandrugs/

Great posts. Thank you.

Generic viagra https://disqus.com/by/canadiandrugspharmacy/about/

Amazing tons of great knowledge!

Viagra sans ordonnance https://offcourse.co/users/profile/best-online-canadian-pharmacy

Cheers, I appreciate this.

Viagra rezeptfrei https://bitcoinblack.net/community/canadianpharmacyonlineviagra/info/

You actually said this effectively.

top rated online canadian pharmacies https://forum.melanoma.org/user/canadadrugsonline/profile/

Information very well regarded.!

canadian pharmacies mail order https://wakelet.com/@OnlinepharmacyCanadausa

Amazing posts, Cheers!

best canadian pharmacy https://www.divephotoguide.com/user/canadadrugspharmacyonline

Nicely put, Regards!

Viagra vs viagra vs levitra https://my.desktopnexus.com/Canadianpharmacygeneric/journal/

Truly lots of wonderful info!

Viagra online http://canadianpharmaceuticalsonlinee.iwopop.com/

You said it perfectly.!

canadian government approved pharmacies https://datastudio.google.com/reporting/1e2ea892-3f18-4459-932e-6fcd458f5505/page/MCR7C

You said it very well..

prescriptions from canada without https://pharmacycheapnoprescription.nethouse.ru/

Many thanks. Valuable information!

Viagra dosage https://www.midi.org/forum/profile/96944-pharmacyonlinecheap

Nicely put, Kudos.

Viagra reviews https://www.provenexpert.com/canadian-pharmacy-viagra-generic2/

Superb content. Many thanks.

Viagra sans ordonnance https://dailygram.com/blog/1183360/canada-online-pharmacies/

Very good information. Regards.

mangalib

mangalib

Viagra cost https://bitbucket.org/canadianpharmaceuticalsonline/workspace/snippets/k7KRy4

Excellent posts. Regards!

Viagra tablets australia https://rabbitroom.com/members/onlinepharmacydrugstore/profile/

Good data. Thank you.

Viagra manufacturer coupon https://www.mixcloud.com/canadianpharmaceuticalsonline/

Thanks, Awesome stuff.

Viagra manufacturer coupon https://sketchfab.com/canadianpharmaceuticalsonline

This is nicely said! !

Viagra vs viagra https://fliphtml5.com/homepage/fhrha

Awesome forum posts, Thanks!

Viagra from canada https://www.goodreads.com/user/show/161146330-canadianpharmaceuticalsonline

You reported it perfectly!

Viagra cost https://myanimelist.net/profile/canadapharmacies

Nicely put. Thanks!

Generic for viagra https://pharmacyonlineprescription.webflow.io/

You stated that wonderfully!

Viagra tablets australia https://www.isixsigma.com/members/pharmacyonlinenoprescription/

Terrific facts. Thank you.