(Judge Dredd Megazine, Rebellion)

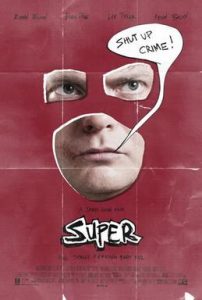

James Gunn’s Super is distinguished straight off by its opening titles, an overwrought, very funny, crayola-violent cartoon. Director James Gunn could have been one of the kids in Super 8; according to his official resume, he was 12 when he disembowelled his brother in an 8mm zombie flick. Later, he wrote Zack Snyder’s 2004 Day of the Dead remake, though I’m one of the few people who preferred his other script that year, for Scooby Doo 2: Monsters Unleashed. But neither of those, nor Gunn’s director debut in Slither, gives any warning of Super. This is a comedy where the humour is as crude as someone beating you on the head with a pipe wrench; no finesse, but you don’t forget it.

Super will be forever labelled as “the other Kick-Ass film”; its premise is just too similar. As in Kick-Ass, an over-imaginative loser-misfit has a go at being a costumed hero for real, dressing up in a shonky super-suit and engaging in orgies of hyperviolence. Both films even share a girl “Robin” character to prove the saw about the female of the species. But now the crimefighters are aged up; instead of Aaran Johnson and Chloe Moretz, we have midlife Rainn Wilson (Mackenzie Crook’s counterpart in the US The Office) and kooky minx Ellen Page (Juno). The violence, while still hilarious, is harder in every sense; Kick-Ass drew howls of outrage for its “15” rating, but Super, with its endless succession of traumatic heard injuries, could never have been less than “18.” The film is scuzzified, washed out; there are gross gags about prison rape, and no last-act jet-packs to offset them.

In the first scenes, Rainn’s character Frank, resembling a doughy Dan Aykroyd, sees his troubled wife (Liv Tyler) stolen from him by a wonderfully sleazy Kevin Bacon, who pops in on him just before to compliment his breakfast skills (“Amazing eggs!”). Frank proceeds to thoroughly abase himself, blubbing through desperate nighttime prayers until his Hallejujah moment (an unforgettable scene, borrowing, of all things, the tropes of anime porn). From this revelation is born the Crimson Bolt; Frank dons a wrinkled, shapeless fart of a costume that would be laughed to death in a cosplay fair. To compensate, he arms himself with a chunky wrench, on the principle that it’s the kind of weapon that you can damage someone with even if you have no fighting skills whatsoever.

Super’s laughs are edgier than Kick-Ass. A preteen Chloe Moretz slicing up drug den lowlives has nothing on Super’s scenes of a middle-aged saddo bludgeoning a guy and his guilty-by-association girlfriend for the crime of – well, you’ll see. For Frank, getting a homicidal sidekick is something approaching therapy, as it lets him see the madness from the outside, though it can’t stop his obsessed mission to get his wife back. The final outcome is somewhere in the middle of the comic and film versions of Kick-Ass, which had diametrically opposed endings. Super feels almost deliberate in the way it refuses to satisfy fans of either, although its big last act shock feels far less cheap than the one in the Kick-Ass comic (the bit with that photo).

Away from Kick-Ass, Super has echoes of Ghost World; both films feature uncomfortable relationships between funny-peculiar fortysomethings (Rainn Wilson, Steve Buscemi) and predatory oddgirls half their age (Ellen Page, Thora Birch). The film seems more interested in pushing borders and plussing gags (there’s a running gag involving an evangelical TV superhero called “The Holy Avenger,” played by Nathan Fillion) than it is in saying anything new. Super also misses an obvious trick, by making it fairly unambiguous from the early scenes that the Bacon character is a true villain and a real threat. Given the recent trend for films set in unreliable inner realities (Inception, Sucker Punch, Source Code, Scott Pilgrim), it seems strange that a picture which is all about mental dysfunction wouldn’t play the “Is the whole plot psychosis?” card.

Perhaps at bottom, Super isn’t the twin of Kick-Ass or Ghost World but rather a film like last month’s indy Kaboom; revelling in its transgressions, flattering the in-crowd, often hilariously funny, but finally with all the substance of a soufflé. But you may well prefer to it to Kick-Ass – it’s punchier, and it’s more interested in breaking rules than in cheering its own sensationalism.

(c) 2018 Rebellion A/S. Reprinted with permission.